I know more about electricity than my husband!

Although in remote coastal communities electricity is often perceived as dangerous and unpredictable, and associated with masculine work, we find that women's experiences with electricity are diverse. We explore how limited access to electricity, as well as related knowledge and skills, affects lives in the community.

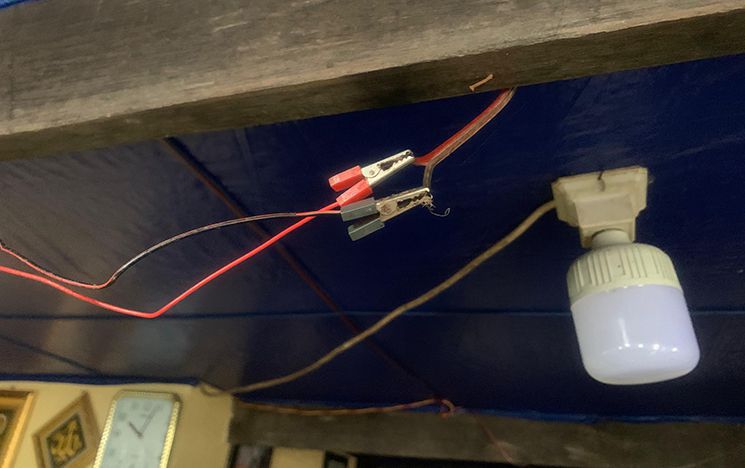

As evening approaches, a woman from Rannu village skilfully connects various cables to turn on the lights, showcasing her knowledge and familiarity with electricity.

Electricity is often associated with men’s work

Women and electricity present a fraught relationship, for electricity is often associated with men and masculine work. As a result, the way electricity is experienced reflects the subordinate and marginalised status of women within their community. Most women view electricity as a complex technology that involves machines and scientific principles requiring advanced technical skills. Additionally, in remote island villages like Rannu, electricity is perceived as dangerous due to its unpredictable and powerful nature. Therefore, it is an activity most do not take an active interest in, with the task often delegated to men. However, if we look deeper, we find that not all women subscribe to this norm in Rannu.

How a lack of electricity affects the community

The limited access to electricity plays a significant role in the marginalisation of remote island communities. In Rannu village, most residents have electricity for only about four hours a day, typically from 6-10 pm. Some individuals have no electricity at all. One older woman reported that she has electricity for just one hour a day. While a few households have solar panels that provide 24-hour access to electricity, this coverage is still insufficient. During our fieldwork, we stay in a house equipped with a solar panel. However, we only have a 10-watt bulb for lighting, which makes reading difficult.

The lack of sufficient electricity as well as knowledge and access to resources also underscores gender inequality in these island communities. These women need access to electricity to empower themselves, improve their circumstances, and benefit the wider community. With greater access to electricity comes greater power and increased opportunities for self-transformation and collective empowerment.

In Rannu village, crocodile clips are commonly used to connect different wires to power the lights.

Diverse experiences, skills and understanding

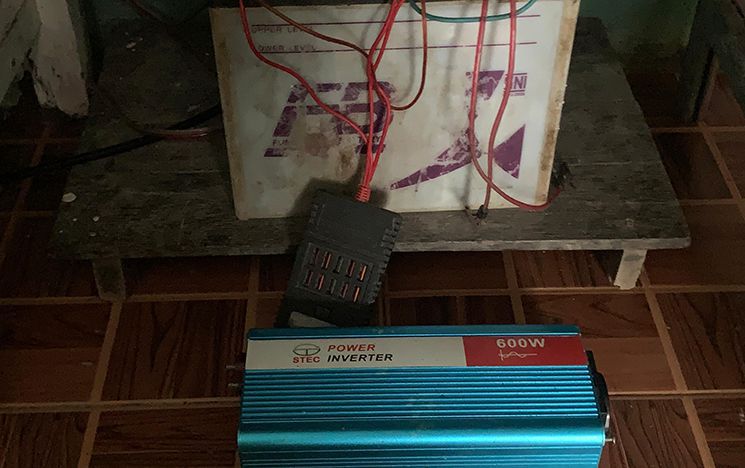

Ground realities reveal that women’s experiences with electricity in Rannu are diverse and not uniform. Some women in the village possess the skills to connect and disconnect different cables to solar batteries (aki) to operate lamps themselves. A few of them also have a good understanding of the basic science of solar energy from rooftop panels. As they also have the option to get electricity from a communal generator, some women can distinguish the different sources and types of energy, cables, how to switch them on and off, the maintenance costs, and the power capacity – specifically, how many watts their electrical devices consume. While they may not fully grasp the technical definition of an inverter, which is used to transform the electricity from direct to alternating current, they understand its essential function. Indeed, such women subvert gendered stereotypes about electricity.

Women would like to learn more and acquire skills

Skills and knowledge about electricity are often gained through personal relationships, such as those with husbands or fathers. However, when it comes to fixing electrical problems, most feel that only men are capable of handling them. Despite this, during a workshop on electricity, the women expressed strong interest in learning more and acquiring the skills and knowledge needed to repair broken electrical installations.

In the workshop, the women identified various issues related to energy sources. Regarding solar energy, they noted several problems, including low battery water levels, broken cables, damaged inverters, and batteries that either boiled or leaked. They also highlighted incorrect wiring as a potential cause of battery explosions.

To address these issues, they proposed several solutions, including regularly refilling battery water, servicing or replacing batteries, ensuring that the capacities of the solar panels and batteries are compatible, and utilising charge controllers.

I want to know how to fix the electricity when there is a broken part. I want to learn how to deal with electricity. I will not be so worried anymore, and when my husband is not at home, and the electricity is in trouble, I can handle it by myself.” Nabila

31-year-old seaweed farmer

Women fix electrical issues

In addition, women’s assumed fear of electricity is unfounded, for they have themselves addressed electrical issues when no one else was at home. Daeng Ratih, a 40-year-old seaweed farmer and tailor, stated that she was not afraid of electricity, cables, or the prospect of electric shocks. She has acquired the least basic skills to operate them well. She has never panicked when something happens to the electricity or solar panels. She has prepared herself in case something unexpected happens.

Daeng Ratih is used to doing “men’s work.” Besides knowing certain aspects of electricity, she made a crab net, which men usually make. When we visited her house, she was making a crab net. She was also a hard worker, working as a tailor in the village.

Daeng Nunu is a 45-year-old woman who works as a shopkeeper and seaweed farmer. She uses two 50-watt solar panels along with a 50-watt battery to power her lighting and television. Daeng Nunu had basic technical knowledge in electricity and confidently demonstrated how to connect the wires to turn on the lights. She learned this skill from her neighbour, not her husband. She jokingly remarked: “My husband does not know about electricity at all.” Interestingly, her husband learned from their neighbour as well. “My husband is not smart" Daeng Nunu exclaimed to much laughter all around. She ended with the statement that headlines this article.

Households in the village utilise a battery and an inverter to activate their solar panels.

The benefits of better access to electricity

In Rannu village, some women are seeking access to sufficient electrical power. This would allow them to enjoy their favourite TV programmes at any time and facilitate household tasks. With an electric pump, they could easily access fresh water. Additionally, having enough electricity is essential for running self-employed businesses, such as producing and selling fish crackers, traditional snacks, and cold beverages. This access would enable them to extend their working hours. Without sufficient electricity, for instance, one older woman shared that she has electricity for only an hour a day, so she spends most of her nights sleeping.

If women have sufficient electricity, they can afford to sleep a bit later or wake up earlier to complete various tasks. This extra time allows them to engage in educational activities, such as reading books or watching informative programmes on television or their smartphones. However, while increased access to electricity can enable women to take on more work, it should not impose additional burdens on them. Additionally, if electricity transforms women’s work into machine-based tasks, such as seaweed processing, strategies must be put in place to prevent women’s unemployment.

A rechargeable portable solar panel which some residents in Rannu village use as their electricity.

Analysis of women’s experiences

From women in Rannu, we learned that we cannot underestimate or overlook women living in remote islands when it comes to electricity. We cannot overgeneralise women’s experiences, assuming that all of them know nothing about electricity. Women in Rannu can negotiate and transform gendered electricity. They needed access to learning activities that could help them build knowledge and skills in electricity and its empowering uses. This learning process should include a gender analysis of electricity in remote islands and coastal contexts to understand its impacts on marginalisation and on empowering women there. This analysis will help us develop and leverage electric resources to drive significant women's empowerment on a remote island. Access to electricity must go hand in hand with the promotion of non-patriarchal gender norms for learning, benefiting both women and men.

As a final reflection, it is crucial to acknowledge the negative impacts of electricity so we can prevent them. While it serves as a vital resource, electricity can be a double-edged sword. For instance, generating power through diesel generators not only contributes to air pollution and climate change but also inflicts noise pollution and strains family budgets. Moreover, if energy access benefits only select women, it will deepen the existing inequalities among women of varying financial means and social standings. Therefore, we must do more than increase energy availability; we must commit to producing energy sustainably and ensure equitable access for all social classes and genders. Only then can we harness the full potential of electricity as a force for positive change.

By Diah Irawaty and Andi Irma Saraswati