The bright and the broken

"With solar power, electricity can last all day. That's what we're striving for".

Broken television set thrown out after a power surge with certain parts taken away and recycled.

A bright past

Virtually every adult we talked to in the Sulawesi islands in Biyawasa and Rannu villages remembered a bright past of cheap solar produced electricity all day, as emphasised by the Biyawasa housewife's words above. Both these places were fortunate enough to receive support from The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) and Mining Company for constructing a 15kW solar plant in their village – from 2013 in Byawasa and 2015 in Rannu. Both had broken down in a matter of years, with the former only after five years; and the latter after six.

Water salination plant that no longer works on a remote island.

Short-lived solar power

In Biyawasa, the solar operation started at the bequest of the community, led by an elementary school teacher of religion and his son-in-law, also a teacher, who put a proposal together for ESDM. The teacher also offered his land as a gift for the community (hibah). He explained:

“We did this because some time ago, PLN (a state-backed electricity provider) came and said each house will get electricity but for a long time it did not happen. So we took the initiative up ourselves.”

The solar plant was duly built but malfunctioned soon after:

“This happened because we didn’t have the knowledge and skills to maintain it. People don’t know the difference between motors, batteries or inverters and mix them up. They weren’t taught well. Eventually the solar plant broke down”.

Disused solar power plant in an off-grid island, lying derelect since 2018.

This was not without his efforts to try and teach people about how to maintain the installation. He continued: “But nobody cared about its proper treatment. I don’t know why people didn’t trust me or follow my instructions. It was very difficult to get through to them.”

Nevertheless, they had fond memories of how island life was like when they had solar electricity all day:

“When it was working, a lecturer came from Marine Science at UNHAS and said, “Biyawasa bersinar” (Bright Biyawasa). Lights were lit everywhere….We could use a tv, fridge; there was music everywhere from sound systems. For men, a sound system is the most important thing. When we had cheap electricity until 2018, it was very noisy.”

This bright past contrasted markedly with a present that was not too bright for people only got regular electricity from two communal diesel generators providing 40 kW and 15 kW of power respectively. They run from 6 to 10 pm every night at relatively high expense. The larger generator too has malfunctioned so that people who it previously served had to fall back on privately hosted solar panels if they had access to them. Others lived in semi-darkness using candles, oil lamps and flashlights for lighting and those relatives who have solar panels for charging their smartphones.

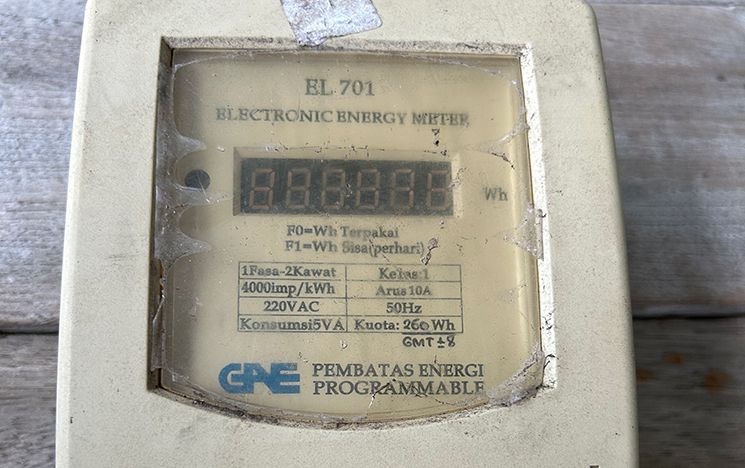

Meters distributed to households to measure electricity provided by a now defunct solar power plant in an off-grid island.

Appliances lie dormant

Meanwhile, their other electrical appliances lay dormant. Even items that no longer worked such as sound systems, rice cookers, and fridges were kept in the house as legacies of a brighter past. This was because there was nowhere to dispose of them on the island; but also because their owners harboured hopes that one day they will have enough finances to get them fixed; or perhaps they could wait for other means of sustenance (“rezeki” in Indonesian from the Arabic “rizq’).

However, we did find in a few instances appliances that were totally ruined were thrown into the sea. This happened in one household as the seventeen year old son recounted: “On a day when it was very bright, there was a power surge from the solar plant and the tv set burst in flames.” They threw the television into the sea. The young fisherman also remarked, “It do not wash back onto the shore with the tide. When I went out fishing, I saw several other television sets languishing in the sea.” Their rice cooker they kept even though they haven’t used it since 2018.

The thick black entwined cables from the solar plant snake their way above the coastal path in Biyawasa. While decapacitated after 2018, they have been redeployed to channel electricity from the communal generators, one mainly serving one end of the long line of coastal homes, the other in the opposite direction. There remain glimmers of hope that pieces of the broken could become revitalised to brighten the island again.

By Raminder Kaur and Della Arlinda Birawa.