CORTH Blog: 4 June 2018

Miranda Marks

Research Associate at CORTH, and Master's Candidate at the University of Leipzig.

Contact Miranda

Beginning in the autumn of 2017, women around the globe have shared their experiences and stories with me about the intrauterine device (IUD). I was particularly struck when two separate American women said they decided to get the IUD because they were nervous that at-the-time newly elected President Donald Trump would fight to remove their access to contraceptive coverage.

For my master’s research, I’ve spoken with women in the US, the UK, Germany, France, and Australia about the small, T-shaped devices that sit inside their uteruses and prevent pregnancy. The women were all under 35 and childless at the time of the IUD insertion, but were raised in many different countries, and have had the IUD inserted in many different situations and for different reasons, some of which don’t include family planning at all. One question I asked the participants at the beginning of the process, was ‘Why did you decide to get the IUD?’. The answers are varied, some wanted the ease, some were recommended it by friends or doctors, some wanted to have lighter periods, some didn’t want hormones anymore. The two American women were facing a shifting political environment, which threatened to limit their access to, or completely remove free coverage of, contraception and wanted security in case that occurred.

The IUD and the U.S.

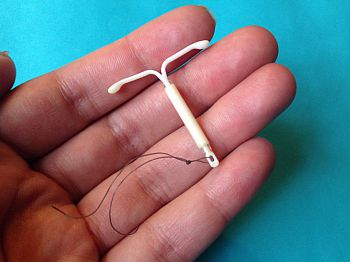

Example of a hormonal IUD

Example of a hormonal IUD

The IUD is a small device that, once inserted, sits in the uterus and prevents pregnancy by creating a “hostile environment for sperm”. The IUD is a 99% effective, long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC), which once inserted it can last between three and twelve years, depending on the specific IUD, and unlike other long-term forms of contraception such as sterilization, when removed allows for pregnancy to occur. It is inserted in-office by a medical professional, and does not require any daily or weekly monitoring. Currently in the United States there are two options for IUDs on the market: hormonal and non-hormonal. ParaGard is the only non-hormonal model currently available, which lasts 10 years and contains a small amount of copper, which is toxic to sperm. There are four hormonal devices on the US market, the Mirena, Kyleena, Skyla, and Liletta, which all release differing amounts of the hormone progestin directly to the uterus and preventing pregnancy for between 3 to 5 years. Unlike the birth control pill, the patch or the other forms of contraception, all forms of the IUD do not require monthly or quarterly doctor visits or prescription renewals. This means that women are generally covered for the entire IUD time-period with minimal medical intervention, in addition to the fact that it is currently available to most women in the US at no cost.

|

Tweets about removing ACA by President Trump before |

Under the 2010 Affordable Care Act, commonly known as Obamacare, the Obama administration federally increased women’s access to contraceptive and reproductive health care services with dramatically reduced or no out-of-pocket costs under their private health insurance. This includes gynecological visit costs, contraception including the IUD, antenatal and post-natal visits, and preventative measures such as cancer screenings and tests. Even before ACA, depending on how long a woman was staying on birth control, the upfront cost of an IUD could be more financially sensible in the same time frame. Considering the price of an IUD can be hundreds of dollars for the device alone, in addition to extra fees for office visits and the insertion, ACA afforded women from many financial standpoints contraceptive and reproductive health care. However, not all insurance plans are included in this coverage, and Planned Parenthood writes that an IUD “costs anywhere between $0 and $1,300” (£960), with this price also depending on the doctor’s office and insurance. Throughout his election campaigning, Trump has run on a platform of “repeal and replace” in reference to Obamacare, a viewpoint strongly held in general by most of the Republican party. Threats of repeal are littered throughout his Twitter and social media feeds, stated with vigor in his speeches, and brought onto the floor of Congress. They were also absorbed into the thought-process through which women came to understand their fragile reproductive coverage. |

Two American Women and the IUD post-Trump

Laurie, a 23-year-old paraprofessional and recent college graduate, had been considering the IUD for quite a while after suggestions from friends, but had never taken the next step to have one placed. In combination with the 2016 presidential election and her partner no longer wanting to use condoms, she decided to have the Mirena IUD inserted in March 2017. She said, “I think I kind of did freak out after the presidential election of not knowing if birth control was going to be covered and wanting something long term that I didn’t have to worry about. You know, getting a prescription for pills you’d have to pay for that if you’re insurance didn’t cover it. It was really a combination of my partner not wanting to use condoms anymore and me wanting to have a long-term birth control method that I didn’t have to worry about paying for that was still covered by insurance”. This ‘freak out’ was rightfully buried within Trump’s consistent and aggressive threats to repeal ACA throughout his campaign, and since his election. Though it has been over a year since the elections, this fear of a conservative backlash against contraception, increasing price and decreasing access to contraceptive coverage, has not subsided. Women such as Laurie are preventatively preparing themselves for the if-and-when of a Republican reform to the current health care system.

Laurie was not alone in her thinking on the cost and long-term reliability of the IUD in the wake of the presidential election. Emma, a 29-year-old attorney, had seen the Mirena commercials on television, but had never considered it seriously until the last election. After hearing from two friends about their decisions to have the IUD inserted, she started to consider it for herself. “When we had this crazy presidential election” she said, “the fate of covering birth control was going to be an issue. I had several friends who went ahead and got IUDs, just because they figured ‘Ok, well at least I’ve bought myself 5 years to see what’s going to happen next’.” Previously on the Nuva Ring for 8 years, Emma had already experienced issues with her health insurance switching to only generic versions of prescriptions. This meant that she had to pay out of pocket for the NuvaRing, as it didn’t have a generic counterpart, which she knew wasn’t feasible in the long run. Fearing a limit to available options and price increase of her contraceptive care, she had the IUD inserted in November 2017. Since then, three more of her friends followed in the same path of reasoning and had IUDs inserted as well. Like Laurie, Emma’s IUD process was completely covered by her insurance, “Up to this point, the whole IUD process has been free. I didn’t have to pay for the insertion, or [the] ultrasound, I didn’t have to pay for any of those things. All of that was provided for with my health care”.

Since writing this post, I have found others discussing online their journeys to the IUD in a post-Trump USA. A December 2016 Chicago Tribune article reports, “Planned Parenthood of Illinois said it saw a 46% percent increase in the number of women making appointments online for intrauterine devices last month after the election compared with the previous November”. According to a January 2017 Business Insider piece covering all the states, “Between October and December 2016, IUD prescriptions and insertion appointments were up 19%”. The trend towards the IUD would appear to not be limited to the two women that I interviewed, but instead the women are within a population that is responding directly to the shifting conservative political climate. When I asked Emma further why the election propelled her decision in this direction she said, “Well because the whole republican party just doesn’t think reproductive rights should be important, and that it should just be a personal financial burden, instead of something the government should protect… A lot of us who have been used to at least very affordable, if not completely provided for, birth control of our choosing for the past decade or so, that’s [kind of] a scary thing to think about”.

The IUD is seen as a long-term reversible and effective contraception which cannot be easily stripped away. These women understand that while they still carry most of the burden of hormonal contraception, their current options allow them to subvert any potential future governmental restrictions through reproductive security that lasts ‘for at least 5 years’. Laurie and Emma’s decisions, and the other women who are accounted for in the statistics, show that women are turning to the IUD as a reactionary measure to an unsure political and health care climate.