Chimpanzees: intentional communication

Our research on chimpanzees indicates that these apes will develop pointing when they are faced with the appropriate environmental circumstances.

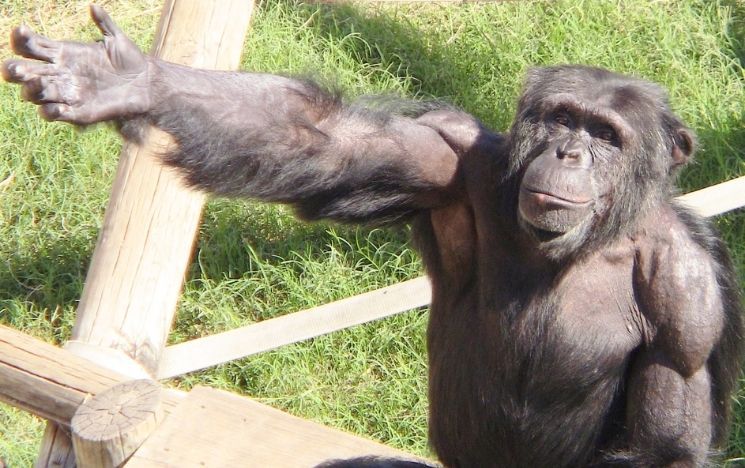

Nahko gestures to a person holding a banana, while looking at the cameraperson. Photograph by Lisa A. Reamer, from Leavens et al., (2015), used with permission.

Chimpanzees: pointing

Dave Leavens has been interested in pointing since he saw a chimpanzee named Clint pointing to a grape outside his home enclosure at the Yerkes Primate Center in 1994. At that time, this was considered to be theoretically impossible—pointing was considered to be unique to humans, a part of their language-learning adaptation. In collaboration with Bill Hopkins and his colleagues, Dave has explored pointing in chimpanzees, asking the following questions:

- is pointing by captive chimpanzees communicative? Yes, they do not point at unreachable items if there is nobody around to see them do it; these are not failed reaching attempts

- is pointing by captive chimpanzees a relatively frequent behaviour? Yes, colony-wide and multi-colony studies establish that 50% to 60% of institutionalised chimpanzees point

- do wild chimpanzees point? Yes, but it is very rare.

In conclusion, chimpanzees point, therefore pointing by humans might not necessarily imply that human pointing is cognitively distinct from animal pointing.

Chimpanzee gestures: intentional communication

Having established that captive chimpanzees point, Dave and his colleagues developed a number of analytical methods to explore the intentionality of these signals, building on the work of developmental psychologists, especially the late Elizabeth Bates, and other comparative psychologists, particularly the ground-breaking observational and experimental work by Michael Tomasello and Josep Call.

Intentional communication was long considered to reflect cognitive capacities that were unique to humans, and the term is used with two distinct meanings in philosophy and psychology:

- intentional can mean ‘voluntary’ and

- intentional can mean ‘about something.’

We have developed a series of criteria that were used in the contemporary scientific literature to define the human onset of intentional communication, at about a year of age.

Our general approach to this research is simple: we have somebody put a banana or a grape outside the home enclosure of a chimpanzee and leave them alone with it, then record their behaviour when a human later approaches them.

Over a series of experiments, we have established that, like human children, chimpanzees look back-and-forth between the human and the desirable food—moreover, chimpanzees in this situation who gesture do this at very high rates: 80% to 100% of these chimpanzees display this gaze alternating pattern, which ties the gestures to both the food and the human. This demonstrates that the chimpanzees’ gestures are about a specific entity.

Also like human children, chimpanzees communicate in different sensory modalities, depending on whether a human is looking at them or not—they will make a sound in the presence of a human who is not looking at them. This demonstrates that chimpanzees have voluntary control over the modality of their signalling behaviour.

Finally, and like human children, chimpanzees persist in their signalling and elaborate their communication when humans purposefully misunderstand their communication. Thus, chimpanzee gestures meet the same criteria for intentionality that are displayed by ourselves—these are voluntary acts, and these gestures are about specific entities.

Dave believes that pointing emerges in apes and humans when a particular set of circumstances are encountered: organisms are restricted from acting directly on the world and they have caregivers who respond to their communicative acts.

Human babies are notoriously helpless for a very long time, relative to other primates, so they develop tactics to enlist the aid of others to act on the world for them. In the wild, great apes are much more mobile in infancy, but when we bring apes into captivity, then they face a similar set of circumstances, unable to act directly on entities outside their enclosures. In this referential problem space, pointing develops in both apes and humans.