West Midlands Heritage Trail

Read about our exploration of the Places of Worship Heritage Trail, an initiative of the Faithful Neighbourhoods Centre in the Birmingham metropolitan area.

Black Country pilgrimage: a short film by Raminder Kaur, Gabriele Shenar and Tarun Jasani

- Video transcript

Prepared by Gabriele Shenar

Filmed during launch of Places of Worship Heritage Trail, Smethwick, in May 2024, an interfaith activity supported by the Faithful Neighbourhood Centre (FNC).

Soundbites from:

Canon Dr Andrew Smith: Director of Interfaith Relations for the Bishop of Birmingham at Church of England Birmingham.

Reverend David Gould: Vicar, Holy Trinity Church

Kulbhushan Rai Prashar: Representative of Durga Bhawan Mandir

Shobha Sharma: Representative of Durga Bhawan Mandir

Harvinder Singh Sehespal: Representative of Baba Sang Ji Gurdwara

Shaikh Nasir Akhtar: Head of Dawah, Tarbiyah & Outreach, The Abrahamic Foundation

Debbie Black: Member of West Smethwick Methodist ChurchGalton Bridge area, beginning of Places of Worship Heritage Trail.

Soundtrack playing, soothing, calming. Title appears, white text against black background: Black Country Pilgrimage.

Soundtrack playing, long-shot of road and group of pilgrims, road sign “Galton Bridge”.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: My name is Andrew, I work for the Bishop of Birmingham, as director of Interfaith Relations and I put this [the heritage walk] together with lots and lots of help and other people.

Close-up of Places of Worship Heritage Trail map.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith (off camera): Good old Galton Bridge.

Sign Galton Bridge and Cycle way.Outside New Hope Christian Centre.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: The longest single-span bridge in the world when it was built 200 years ago… So let’s head that way.

Left pan from group to road.

Pan left to New Hope Christian Centre.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: This is the first stop on our trail. And some of the places we are gonna go to are big and well-visited and some are small but faith-full congregations, and so part of what we are gonna see is the different ways people are worshipping, and their faith communities are. And this is the New Hope Community Christian Community Centre. It is part of what is called the Pentecostal Tradition, particularly the ELIM Church within the Pentecostal tradition.

Close-up of heritage trail map.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: So it is quite a small congregation with two congregations. In the morning, they have one that is predominantly Caribbean and also some white British folk, and in the evening it is a Tamil congregation.

Exterior and interior of The Hindu Cultural resource centre Durga Bhawan, Smethwick.

Pilgrim group walking towards Durga Mandir on Spon Lane S, Smethwick, Durga Bhawan temple in distance.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: And this was originally the Spon Croft pub. They bought the old pub.

Exterior of Durga Bhawan Temple, pilgrims at entrance door.

Entrance hall of Durga Bhawan Temple, shoe rack, pilgrims take off shoes.

Close-up golden sign “Hindu Cultural Resource Centre Sandwell, Durga Bhawan, Inaugurated in honour of Sanjay Puri, by Mananiya Nathu Ramji Puri, Philanthropist and Industrialist of Puri Foundation, 30th June 2002.

Inside temple, communal area, Andrew is welcomes with floral garland.

Andrew Smith: Oh, thank you that is a great honour.

All present applaud, pan right to pilgrims seated a table.

Representatives of Durga Bhawan Temple standing during reception speech by Kulbhushan Rai Prashar.

Soundbite:

Kulbhushan Rai Prashar: Eventually, the pub went for sale, we bought that, and we made the decision to put a temple on that building. But that building was solid building. But somebody put it on fire. So we had to demolish that. So many hard period go by… but we are, we believe that things happen, those things happen that God want.

Inside temple sanctuary, various gods at shrine, Hindu family, girl rings bell, various of Hindu worshipers performing ritual act in front of gods.

Soundbite in front of Ganesha statue.

Shobha Sharma: (with group of pilgrims during short tour of temple sanctuary) Anything we start off, we start off with Ganesha. And then we move into… this is Lord Shiva… bathing him with milk and water.

Hindu woman performs ritual act, bathing Lord Shiva with milk and water.

Statues of Hindu gods.

Soundbite:

Shobba Sharma: This is the main goddess, she is the wife of Lord Shiva.

Shobba Sharma: We have Guru Nanak Dev ji and Guru Gobind Sing ji here…(Shobba folds hands in prayer) Hinduism and Sikhism are quite closely related, we celebrate all the same things.

Shobba Sharma: (standing with Muslim woman in front of picture) Guru Nanak Dev ji was a Hindu first… the he took a little bit of Islam and a little bit of Hinduism and then 500 years ago Sikhism was born.

Hindu worshipers and non-Hindu pilgrims are sprinkled with holy water.

Longshot of worshipers and people leaving temple sanctuary after aarti (prayers), Hindu man distributes puja.

Outside Jamia Mosque Oldbury Road.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: This was a working men’s club selling alcohol… and it is now a mosque. They offer two Friday services on two sermons and one is always in English, as with most mosques now as it makes the younger generation understand their faith.

Marshall Street Smethwick.

Long shot of blue plaque Malcom X, pan left to pilgrim group.

Pilgrims: MalcomX.

Soundbites:

Andrew Smith (not in picture): We’re gonna walk that way round…

Debbie Black: Malcom X. He was killed in 1962…. I was nearly three, three and a half. But my mum saw him because we lived down the street.

Andrew Smith: In 1965, …. And a party came here.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: He was invited by Mr Avtr Avtar Singh Johl, former general secretary of the Indian Workers’ Association. He was the man who made the invite. And it was partly, and this is a bit like what you were telling me earlier, when you were telling me about the plan for segregated housing wasn’t it.

Andrew Smith (not in picture): They said he was opposed, he opposed the segregated housing idea.

Pilgrim takes picture of blue Malcom X plaque.

Soundbite:

Shobha Sharma: There was a lot of unity, people in the 70s and 80s. People used to go to pray together, we used to go to churches. People would come to our Gurdwaras and temples and everything. There was nothing… and then people started exploring identity and religion and like that. But it was really good. The community was good.

Andrew Smith: There was that good bit … but then there was under that, there was this racism going on.

Pilgrim in grey blouse: yeah, yeah.

Andrew Smith: It was really quite severe, I remember Lenny Henry on the telly one time … because he was near here… This is how bad it was, we had to have Malcom X come… (all laughing)

Close up front door, various of houses in Marshall Street, over shoulder pilgrims walking down Marshall Street and commenting on housing styles

Debbie Black: There was a corner shop down here

Pan left, close-up sign Marshall Street, Smethwick B 67, Sandwell.

West Smethwick Methodist Church, Holly Lane.

Sign Holly Lane, group standing near sign, people chatting, man crossing ST Pauls Road.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith (off camera): people are talking about Malcom X being here and that, but there was round the corner there was a church and a youth club where they came together … that is really an important part of the story isn’t it.

Inside Methodist church, congregation singing.

St Pauls Road.

Exterior of Islamic Learning Centre Topsham Road/St Pauls Road.

Pilgrims walking in St Pauls Road.

Baba Sang Ji Gurdwara.

Exterior of Baba Sang Ji Gurdwara, tilt down, pan right to group waiting outside gurdwara.

Inside Baba Sang Ji Gurdwara, door with sign Langar Hall, pan right to group, Andrew and Shobba.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smiht (to Shobba): You want to lead the way, so we know what we are doing… and then we can sit in the corner on chairs.

Over shoulder Shobba walking into Langar Hall, sound of prayer, various of people eating in langar hall, group so pilgrims eating seated on floor, close-up of plate and food

Inside lobby of Baba Singh Ji, group walking upstairs.

Soundbite:

Harvinder Singh Sehespal: We tend not to do our bath towards Siri Guru Granth Sahib because that is a living spiritual leader.

Harvinder Singh Sehespal: Waheguru Jee Ka Khalsa Waheguru Je ka Fateh. That is our traditional Sikh greeting, and it’s all to do with Waheguru. In our believe system, Waheguru is the one God and we obviously believe that different prophets, different messengers are all respected, and they are all mentioned in the Guru Granth Sahib. This gurdwara site is unique because the community got together in 1993, 94 and they purchased the building Empire which was quite a historic theatre and if everybody is happy to going up the stairs, there are a few stairs, I can show you the Sach Kand. What you will see, is like beds, on an actual bed we place the Guru Granth Sahib out of respect, cover it with a duvet, look after, make sure you know it is an airconditioned room, with the utmost respect.

Cutaway beds in Sach Kand, bedroom for holy books in need of repair.Guru Nanak Gurdwara

Exterior of Guru Nanak Gurdwara, pan left to pilgrim group

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: A nationally significant gurdwara, the first purpose-built gurdwara in Britain, possibly Europe, certainly in the West Midlands, one of the first purpose-build gurdwaras, and this was originally a Smethwick congregational church built in 1885, that closed down in 1961, it was derelict for a long time. The Sikh community bought it and used it as a place of worship and the Gurdwara then did the statue in 2016, the Lions of the Great War to commemorate all the soldiers from the Indian subcontinent, it is dedicated to Sikh Solders, but it is definitely for all the soldiers from the India Subcontinent who fought and died in world wars in huge number, as we can see in the plaque underneath there which a local artist did as part of the celebration of Guru Nanak, 550 years before.

Guru Nanak Memorial Stone.

close-up memorial stone: This tree was planted on 6th November 2019 to mark the 550th anniversary of the founder of the Sikh faith Sri Guru Nanak Dev Ji, as a mark of the fellowship between faiths by Guru Nanak gurdwara and Holy Trinity Church Smethwick in partnership with EcoSikh.

Soundbite:

David Gould (off camera): This started out as a conversation between here and Guru Nanak next door. The result was, and through Andrew’s good offices, that the Sikh leaders from Birmingham and beyond came here one evening, we had a ceremonial planting of the tree with the Bishop of Birmingham and the Sikh leadership. Fabulous evening, the church was absolutely packed with Muslims and Sikhs, there was hardly a Christian to be found. That is a measure of the cooperation.

Tilt up Holy Trinity Church.

Over shoulder group walking to Holy Trinity Church

Holy Trinity Church.

Soundbite and cutaway to exterior of church.

David Gould: There were five churches in this town church of England and then they were closed to leave this one. when I got here, they all sat in their groups, depending on which church they had come from. There were only twelve or thirteen people still alive from the people inherited and they have been replaced by people from Asia, Africa, some Brits, and the result is that it is now a black majority church. I am happy to answer any questions.

Group inside church applauding, exterior of Holy Trinity Church, David Gould walking on street with Shenar.

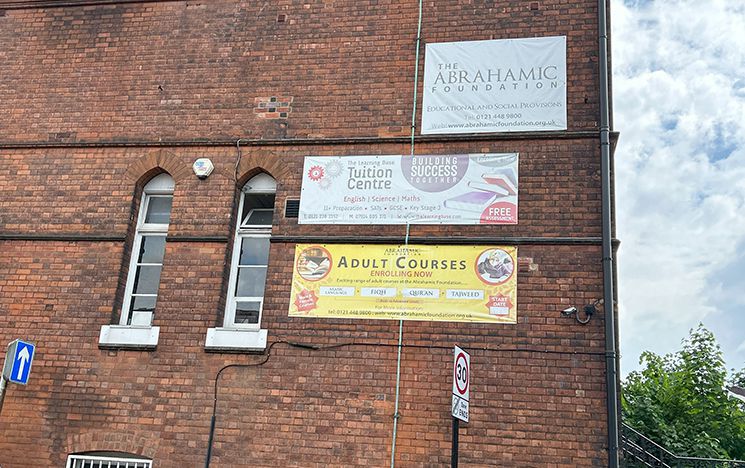

Abrahamic Foundation.

Exterior of Abrahamic Foundation with large sign.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith (off camera): Welcome to the outside of the Abrahamic Foundation.

Nasir Akhtar: (partly off camera). In a nutshell, we called it the Abrahamic Foundation …

Nasir Akhta: We set it up because we were getting a bit tired of spaces, mosque spaces, our spaces of being spaces that were only for worship, and we wanted to create a space that was inclusive, a space that went beyond community languages. So mosques are based generally on ethnic and language grounds, the Bangladeshi mosque, the Yemenite mosque, the Afghan mosque, the Gambian mosque, whatever you see the connection with the mosque and the language which connected to that centre, we felt that we are British-born and we are a bit tired of these languages and these ethnic labels, we go to school with our friends an colleagues we don’t really see anyone differently, we just want an English mosque, if I sort of use that…, and English Muslim British mosque that is really there for serving all the community.

Andrew Smith: Thanks Nasir, this really is an amazing place, so always worth a visit

over shoulder group walking in street, exterior of Smethwick Council House

Alexandra Park Smethwick.

Ice cream van in Alexandra Park.

Andrew Smith: And if anyone wants to have an ice cream, feel free to have one.

Jamia Mosque.

Group walking outside mosque.

Exterior of Jamia mosque.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: The community did not have a mosque round the corner that seated, well, they had to accommodate 500 or 700 people for prayer but it was. So in 2005 they purchased this piece of land and started waiting on it, they spent nearly 14 years raising the money and building it, parts of it came from Turkey. The marble came over from Turkey, it was cheaper, and they extended it as they were building it, as they thought it wasn’t quite big enough (smiling). So their original project of two and a half million came to just under nine(9) They have 20 paid staff. It is an enormous operation. They do quite a lot of community activities.

close-up Info sign: Purpose Built New Mosque Project Smethwick.

Sign urgent Masjd Fundraising Appeal.

Close-up layout mosque.

Ceiling and calligraphy Arabic.

Soundbite:

Nasir Akhta (off camera): We believe in one God and Mohammad is the messenger of God. And this id one of the main verses of the Quran that talks about God’s oneness and power.

Group walking in street.

Smethwick Baptist Chapel.

Exterior of Baptist Chapel, man walking out of church, tilt up church.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith (off camera): and money came from the compulsory purchase of Canon St Church in Birmingham, to build Corporation St and that money was given to eight Baptist churches around Birmingham, and this is one of them. …

Group standing outside Baptist Chapel.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith: So when they demolished the one in the city centre, this was the fruit of that.

So the other one where we started off this morning, they had the Tamil Christians on a Sunday afternoon and they (Baptist church) have the Punjabi Christians on a Sunday afternoon. So that kind of variety.

Andrew Smith: So, here we end this… our final stop, so thanks very much for coming. Down there it goes to Galton Bridge Station .

Group applauding.

Pilgrims walking along canal near Galton Bridge.

Galton Bridge as seen from ground.

Soundbite:

Andrew Smith (off Camera): The longest and highest iron girder bridge in the world. However, as it is the end of the walk, we have to get up there. So we have a bit of a climb now.

Shenar: you did not mention that…

Andrew and Shenar walking along canal near Galton Valley and Galtob Bridge.

Sign Galton Bridge on the Revolution Walk.

Group walking up to Galton Bridge, green footpath.

Soundtrack playing, soothing, group walking past graffiti and on bridge.

End shot of group walking fading out.

Credits

A sincere thank you to everyone we met and walked with during the Places of Worship Heritage Trail launch in Smethwick in 2024 – an interfaith activity supported by The Faithful Neighbourhoods Centre (FNC) – and to those in the places of worship for their warm hospitality.

Special thanks to:

Canon Dr Andrew Smith:

Reverend David Gould

Kulbhushan Rai Prashar

Shobha Sharma

Harvinder Singh Sehespal

Shaikh Nasir Akhtar

Filmed by

Raminder Kaur

Gabriele Shenar

Edited by Tarun Jasani

Logos: Pilgrimonics, Leverhulme Trust, University of Sussex.

The Urban Transcendent amidst a Heritage Trail in the West Midlands

Gabriele Shenar and Raminder Kaur

‘Reconciliation starts in our towns.’

Be it in a fragrant flower penetrating an asphalt road, a ladybird landing on a fingertip, or a shaft of light reflecting the ripples onto the underside of a canal bridge, the transcendent is all around us in urban locales even in Britain’s former industrial heartlands, colloquially referred to as the Black Country.

Moreover, as Canon Dr Andrew Smith, Director of Interfaith Relations for the Bishop of Birmingham, maintains, the transcendent is especially encountered in the many urban places of worship.

In May 2024, we had the opportunity to explore such phenomena on an interfaith heritage trail in one of Sandwell’s super-diverse neighbourhoods, Smethwick, a district adjoining Birmingham, as part of our ‘Pilgrimonics’ research on pilgrimage, economics and related circuits of exchange.

The Places of Worship Heritage Trail is an initiative of the Faithful Neighbourhoods Centre. Along with Andrew and Reverend David Gould from Smethwick’s Holy Trinity Church, community leaders including Shobha Sharma, Kulbhushan Rai, Harvinder Singh Sehespal, and Shaykh Nasir Akhtar acted as tour guides on the day.

The interfaith trail connects otherwise separate community hubs and residents to learn with, and from each other, to find similarities and differences, and to eat and even pray together. Those who engage in activities beyond the annual interfaith week, understand that there is a need for more community interaction to think ‘not of just one community but a community of communities’ as David described it—one that crosses divides between religion, ethnicity and race.

Beginning with the monumental cast-iron Galton Bridge that was opened in 1829 now tucked away behind an A-Road, we walked for several hours on a rare sunny Saturday. After an informative stop outside the New Hope Christian Centre, the urban ‘pilgrims’ went into the Durga Bhawan Mandir, were treated to tea, and then sprinkled with holy water during an aarti ritual.

We then went past the Oldbury Jamia Masjid as we headed towards the West Smethwick Methodist Church where we chanced upon a musical performance. We ventured towards the Sikh Gurdwara Baba Sang Ji - once a theatre showing home-grown star Charlie Chaplin’s performances, and a place where former prime minister John Major’s performing parents worked. Here, we sat down on the floor to partake of a communal meal (langar), originally intended by Sikh gurus to break down barriers between castes and creeds. After seeing the 300 holy scriptures from British gurdwaras sent here for repair, we went past the Guru Nanak Gurdwara down the road, one of the largest in Europe with its all-day programmes and religious and musical specialists from India.

Next, we walked up a hill to the Holy Trinity Church established in 1838. On the lawn, we saw a tree planted in 2019 to commemorate Guru Nanak’s 550th anniversary in an act of solidarity to the nearby gurdwara. Noting that the gurdwara gets ten times more visitors than the church, David acknowledged that they were the ‘minority group’ in Smethwick. We were then taken to the Abrahamic Foundation that conducted their services in English to communicate to younger Muslim generations.

We ended up inside the largest mosque amongst West Midlands’ numerous mosques, the Jamia Masjid, marvelling at its grand ceiling, calligraphy and vast rooms, followed by a fond farewell outside the nearby Smethwick Baptist Church.

Participants traversed the past as they navigated landmarks to do with Smethwick’s industrial, colonial and migrant histories, once called the ‘workshop of the world’. This included the Smethwick Glassworks of Chance Brothers that had manufactured sheet glass for London’s Crystal Palace and Big Ben; a clocking-in system for bus companies that began to employ migrants in the 1960s; and Marshall Street visited by the African-American civil rights activist Malcolm X in 1965, only nine days before his assassination in the USA—he was invited by Indian Workers Association’s Avtar Singh Jouhl against the toxic racism and housing and leisure segregations that blighted Britain. A blue plaque marked a very ordinary street with an extraordinary legacy that led to the 1965 Race Relations Act.

Such landmarks raise interesting questions about the very conceptualisation of heritage including religious, socio-political and everyday insignia. They are especially pertinent in the layering of old buildings—those that have been repurposed as with the Guru Nanak Gurdwara that used to be the Smethwick Congregational Church (established 1855) and converted in the 1960s to become a Smethwick spectacle. In another instance of interfaith alliance, the Durga Bhawan Mandir, formerly the Spoon Croft pub, was bought with the help of the Sikh community in the 1990s and transformed into a Hindu place of worship.

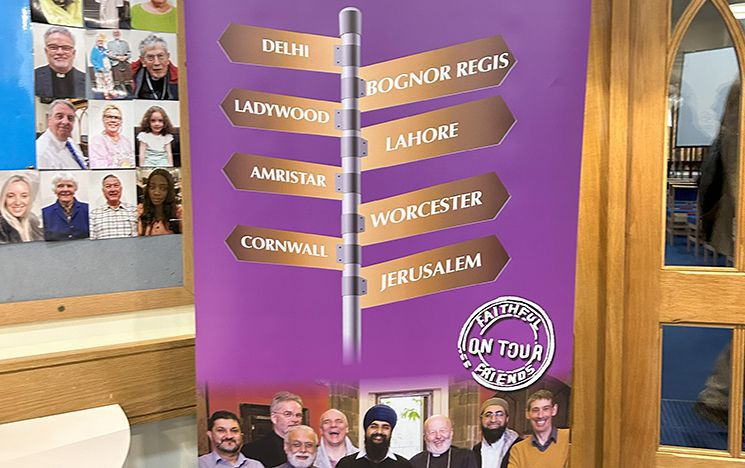

At the end, some of us continued our walk along the Smethwick section of the Worcester and Birmingham Canal, a reminder of the serene beauty that the urban landscape can harbour, and a welcome sanctuary from the noisy hubbub of the busy traffic-congested streets. Fittingly, the canal sported a narrowboat named Shanti (Hindi/Panjabi for peace). We also learnt that, as part of the Faithful Friends on Tour, some faith leaders had visited the Golden Temple (aka Harmandir Sahib), the holiest Sikh shrine in India, staying in the Nishkam International Centre that is managed by Birmingham’s Guru Nanak Nishkam Sewak Jatha gurdwara. As guests of Birmingham’s Sikh leaders, they received special access to the sanctum sanctorum in the centre of the holy pool, sarovar.

Andrew was even compelled towards carrying the palki with the holy scripture, the Guru Ganth Sahib, to its overnight resting place in the Akal Takht building in the complex. Interfaith trips to India and Israel/Palestine in the past also included members of Birmingham’s Jewish community although there are no synagogues in Smethwick.

Altogether, the Places of Worship Heritage Trail enabled collaborative ethnography through walking and talking, and an immersion into the multi-sensorial reality of Smethwick’s heritage markers, large and small, local and transnational. Another benefit was obtaining different angles through our camera lenses as we recorded places and people for a film to share with participants. Afterwards, we observed youth setting-up tents and tables outside Gurdwara Baba Sang Ji for the Nagarkirtan procession - literally meaning traversing the town with spiritual song. But that is another story of urban transcendence.