Tradigrades and the Development of a DIY Digital Microscope

This is the first illustration of a tardigrade by Goeze; ‘Kleiner Wasserbär’ (Bonnet and Goeze, 1773)

This is the first illustration of a tardigrade by Goeze; ‘Kleiner Wasserbär’ (Bonnet and Goeze, 1773)

Tardigrades are some of the most fascinating creatures known to man, and yet many people don’t know they even exist. Microscopic in size, tardigrades have developed a peculiar set of skills which are unlike any other organism on the planet. They were first described in 1773 by Goeze (see adjacent picture), who initially called them water bears, before Spallanzani gave them the name Tardigrada (slow stepper) in 1776. There are over 1,000 known species of tardigrades found all over the planet, but there are bound to be thousands more yet to be discovered.

Over the last 240 years, tardigrades have provided a fascinating insight into many areas of biology. Tardigrades are most well known for their ability to dry out and enter the 'tun state' in which some species are able to effectively pause their metabolism. In this state, tardigrades can survive very high and low temperatures, and extreme pressure, even over extended periods of time. Most famoulsly, tardgrades in their tun form can even survive the complete vacuum, and X-ray bombardment, of outer space. Their extreme abilities have led to many people questioning their evolutionary provenance - but if they do come from outer space, they still use the same DNA triplet code that we do.

Research from Japan (Hoshimoto et al (2016) Nat Comm 7 doi:10.1038/ncomms12808) identified a tardigrade protein which protects DNA from X-ray and desiccation damage; when expressed in human cells this protein confers the same protective function. Perhaps this protein, and other related proteins could be used to protect patients undergoing radiation therapy. This could be the start of an exciting era of discovery of other useful proteins hidden in the tardigrade genome.

The entire ‘Picroscope’ assembly, with the stand on the right and the 7 inch touchscreen monitor on the left

The entire ‘Picroscope’ assembly, with the stand on the right and the 7 inch touchscreen monitor on the left

Not only do they possess incredible and unique survival abilities, they are also hugely popular with the general public, as well as with students right the way through from primary school to postgraduates, making them a great species for outreach work and teaching microscopy.

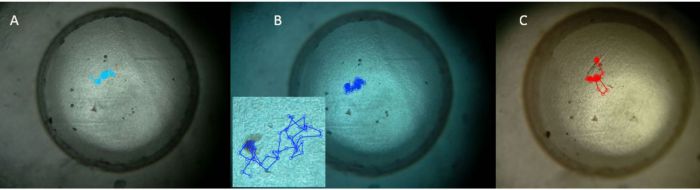

We have been studying the parthenogenic species, Dactylobiotus dispar. Our current project is investigating how the movement behaviour of tardigrades changes in response to changing temperatures in their local environment (motion paths of a tardigrade exposed to different temperatures shown in the banner image). As part of this project, we have developed a low cost, digital microscope (see adjacent picture). The microscope is controlled by the Raspberry Pi, an inexpensive, credit-card sized computer which allows for the use of external sensors to monitor the environment. This microscope has been designed with schools and colleges in mind, and can easily be reproduced using materials that can be purchased in a high street DIY store (total cost for the microscope about £50). This work has been recently published (Kent and Bacon (2016) School Science Review 98: 75-82). School Science Review is widely read by Biology teachers in the UK; our aim is to encourage pupils, working with their teachers, to build their own microscopes for the observation of tardigrades, and other micro-organisms.