CORTH Blog: 08 January 2021

Karin Båge (CORTH member) is a doctoral student in global health at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden. Her project explores global quantitative measures, such as the World Values Survey, as useful tools to advance understanding of values and social norms related to sexual and reproductive health and rights, with a particular focus on reproductive empowerment. She has an MA in Visual and Media Anthropology from the Freie Universität in Berlin, and a BA in International Relations and Social Anthropology from University of Sussex.

The author attending webinar on Zoom.

The author attending webinar on Zoom.

This is a blog post about a recent doctoral course I took in November of 2020 on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). As part of the course, I kept a reflection diary and this blog is based on some of my notes.

Sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) engages many people, if not everyone. It does so because it touches upon some of the most intimate and private aspects of our lives as well as some of the most life-changing decisions we can make, like starting a family. Because of this impact on families, children and demography, SRHR is also highly political.

Topics such as adolescent sexuality, sexual orientation and gender identity as well as abortion and gender-based violence can at times, and in certain contexts be very sensitive and controversial subjects. Research on these issues can therefore be quite challenging. Acceptance from stakeholders, interest from funders and support from colleagues is not necessarily a given in comparison to other topics related to health or human rights. As such, researchers may find themselves looking for a supportive community, one that stretches beyond geographical borders and disciplinary boundaries, that can provide an encouraging environment; to inspire researchers to continue their work, and that also has an understanding of, and a curiosity to learn about what different SRHR issues may mean for health, rights, justice and quality of life for different people in different contexts.

In a recent online doctoral course provided by four universities in the ANSER network (Academic network for sexual and reproductive health and rights policy), students, including myself, from a wide range of contexts and professional backgrounds came together to learn more about this field, and in the process (and in the midst of a pandemic) created a version of such a community (photo 1).

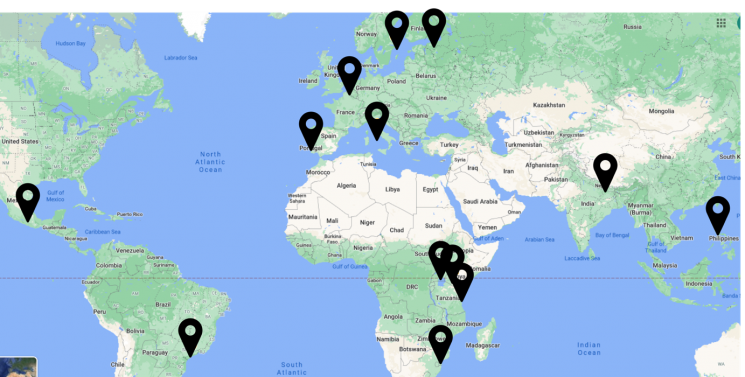

Global sexual and reproductive health and rights; methods, concepts and implications for policy and practice brought together eight coordinators and 34 doctoral students from Ghent University (Belgium), Karolinska Institutet (Sweden), NOVA National School of Public Health (Portugal) and the Technical University of Kenya (Kenya) over a period of two weeks in early November 2020, to discuss the latest SRHR research - completely online. We, the students, research a broad range of topics related to SRHR, including the effects of environmental chemicals on female reproductive health, parent to child communication on sexual and reproductive health in Uganda, factors influencing cervical cancer screening among migrant populations in Portugal, endometrial cancer, and comprehensive sexuality education and how socio-political conflicts arise from its content, implementation and policies in Kenya. Throughout the course, we were asked to consider how the presented theories related to our specific research project and to reflect on the ethical aspects of our chosen methodology as well as possible policy implications of the results. We were also given an opportunity to explore new research methods to adapt to our own research project.

All of the topics were interesting and relevant, but there were two discussions that I remember the most. First, it was eye-opening to hear what other course participants thought of the need for a new, broader definition of SRHR. My break-out group discussed the importance of how this new definition emphasized choice and non-medical dimensions, such as the social and emotional aspects of SRHR. Several group members also brought to our attention how the definition recognized the progress actually made in recent decades since the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994. The global discussion or ‘culture’ on these issues has moved forward in such a way that what may have been accepted as ‘normal’ (or at least tolerated as acceptable) a few decades ago is now considered to be a problem. Two of the most salient examples may be the rights of LGBTQ people, but also the understanding of sexual harassment and the #metoo movement’s effect on how this issue is understood and discussed (at least in certain contexts). We discussed that, with the updated definition of SRHR, a new baseline understanding of what ‘a problem’ is, has been established, and as a global collective, we can recognize that an issue is a problem at an earlier stage relying on more subtle signs than before…. At least in theory.

The other session was the high-level panel on current challenges and opportunities in SRHR. While it unsurprisingly addressed many aspects of COVID-19, Dr. Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli’s also raised other issues that impede progress. His call for a much more transparent discussion on failures in research was very inspiring. He made the argument that in order to move beyond the status quo and turn challenges into opportunities, researchers and practitioners need to be much more open with their process, including failures and what could have been done differently in their projects. One of the course coordinators asked him how one can create a research environment in which it is safe to share failures and mistakes. His response was to change research culture as such, rather than leaving it up to a few passionate individuals; there is a need to integrate skills in expressing, receiving and addressing failures into formalized education and research training. I found this discussion to be very inspiring. The call for more transparency around failures in a supportive way is really an opportunity to develop empathy and community, both crucial for research especially in SRHR given its juxtaposition in the private and the political.

The course did not only have a wide approach to the content, but also to the way it was delivered. It emphasized learning from a multitude of sources; beyond lecturers and invited guests, doctoral students were encouraged to learn from each other. The course design leveraged the online tools and teaching techniques that had been developed under the restrictions of the pandemic, to maximize the benefits of an international course delivered entirely online. Each day we all met for two by two hour Zoom sessions. We had to prepare individually by reading relevant literature and watching pre-recorded lectures. Once everyone was online together, the focus really shifted to interaction and breakout sessions lasted up to 45 minutes. The groups were always mixed and as such there were always opportunities to learn from students working and researching in different contexts.

A map showing the geographical diversity of course coordinators, teachers and students

A map showing the geographical diversity of course coordinators, teachers and students

We were assessed in a final assignment and webinar. At the start of the course, we had to hand in a draft manuscript or research protocol to our local course coordinators, which we then had to work on during the course, applying the methods, concepts and other knowledge that we gained throughout the course. It was then shared with a peer who provided feedback orally in a final webinar. This was a good learning strategy and appreciated by many, as structured, constructive and supportive reviewing skills was something that we all wanted to develop further. The other graded assignment was to submit a reflection journal, in which we had to document and reflect on what we had learned in each session. Crucial to successful online international learning on SRHR was clearly defined preparatory work, break-out sessions with few, but mixed students, that lasted for a substantial amount of time and linking it to the final assignment.

Two weeks passed by quickly and due to the wide approach of the content, the course could definitely have been longer, or run over a longer period of time to really allow students more time to engage with the literature and the sub-themes discussed. Next time, I hope even more emphasis will be placed on theories of power such as feminism, postcolonialism and other relevant perspectives on which to relate one’s research questions and results.

In this course, there was consistent focus on the importance of learning (rather than performing) by creating community and networks to enable understanding across contexts, experience and professional background and discipline. SRHR is an umbrella term that includes an extremely wide range of topics and perspectives, as such the diversity of research questions and methods that pertain to this area of study necessitate discussions between all kinds of people and backgrounds. If we are to truly develop understanding of this highly personal yet very politicized area of human life, we, researchers, need to not only meet across disciplinary siloes, but also do so in a supportive way. We should really take the opportunity to do so through education and online tools. Platforms like CORTH and ANSER have a crucial role to play in facilitating supportive communities in SRHR to encourage and sustain such connections and promote the development of relevant knowledge, particularly in times of repression on these vital issues.

Take home message:

1. Use new tools for online international SRHR education

2. Use new online tools to create a supportive, international and interdisciplinary community for SRHR research

3. Design courses that focus on interaction between participants

4. Design courses that are open to many disciplines and intentionally promote cross-disciplinary collaboration and learning

5. Intentionally integrate learning activities and assessments in which participants and students can develop their empathy including ways of communicating it effectively

References:

Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, Basu A, Bertrand JT, Blum R, et al. Accelerate progress-sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher-Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2642-92.