The curious absence of services trade

With exports of services worth £220 billion to the UK economy, we need to make sure that Brexit discussions don't ignore this vital component of the UK's trading environment.

Dr Ingo Borchert is Lecturer in Economics and a fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory at the University of Sussex.

© User:Colin and Kim Hansen / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

The UK car industry’s fears over Brexit have been widely discussed in the media (see Peter Campbell’s piece in the FT), and for a good reason. Then again, as the panto season is approaching, one is tempted to shout “Look behind you!”. What is hiding from the limelight of public discussion is the fact that the overwhelming majority of economic activity in the UK pertains to services (close to 80% of GDP), and that international trade in services too constitutes a sizable share of overall trade (exports of £220 billion in 2014, compared to £295 billion in merchandise exports).

Services and services trade policy-making are curiously absent from the Brexit debate. This needs to change.

From telecommunications to retail distribution for British consumers, and from financial to legal services for firms, the economic significance of services trade is evident. Yet services and services trade policy-making are curiously absent from the Brexit debate. This needs to change, and a good starting point is an appreciation of the diverse ways in which services matter for the British economy.

To begin with, loads of services are being traded across borders directly, for instance by purchasing (or selling) an architectural blueprint, a legal opinion, or any form of insurance. The biggest items in this regard for the UK economy are business services, financial services, travel (which includes tuition fees of foreign students in the UK), transportation and telecom/information services (Table 1).

Given the prominence of financial services, it may come as a surprise that services trade is in fact much broader; indeed, the most traded category of other business services encompasses a rich set of producer services such as research and development, design, marketing, and technical or professional services.

Table 1: UK Trade in Goods and Services, by Sector and Destination, 2014

| Exports | Imports | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | EU-27 | World | EU-27 | |||||

| Value (£ m) | Share in total | Value (£ m) | Share of EU | Value (£ m) | Share in total | Value (£ m) | Share of EU | |

|

Services of which: |

219,759 | 42.7 | 81,275 | 37.0 | 130,619 | 23.8 | 64,154 | 49.1 |

| Other business services | 57,135 | 11.1 | 18,329 | 32.1 | 35,508 | 6.5 | 15,251 | 43 |

| Financial services | 49,223 | 9.6 | 20,208 | 41.1 | 10,004 | 1.8 | 3,614 | 36.1 |

| Travel | 28,341 | 5.5 | 12,075 | 42.6 | 38,428 | 7.0 | 22,367 | 58.2 |

| Transportation | 26,706 | 5.2 | 11,891 | 44.5 | 19,369 | 3.5 | 10,368 | 53.5 |

| Telecoms, computer, information | 16,332 | 3.2 | 7,517 | 46.0 | 9,413 | 1.7 | 5,418 | 57.6 |

| Merchandise goods | 295,432 | 57.3 | 147,618 | 50.0 | 419,104 | 76.2 | 226,480 | 54.0 |

Source: ONS Pink Book 2015; author’s own calculations.

The EU is the largest trading partner for virtually all of these services. More than one-third of UK services are exported to the EU, and this share rises to nearly 50% if Switzerland is included as it is a major destination for UK financial services exports. Conversely, half of all services imports originate from the EU.

These shares underscore how tightly the UK is intertwined with continental Europe. The legal frameworks that underpin all these services trade flows are diverse and often fairly complex. The ramifications of Brexit for services trade should be carefully considered so as to avoid unwelcome or unforeseen disruptions.

When British car makers point out that individual parts such as bumpers or injectors criss-cross the Channel several times before being assembled into a car, the primary message is that even seemingly minor trade barriers as might result from Brexit would be greatly magnified in the presence of back-and-forth supply chain trade. That point is well taken, but the message runs deeper. The question really is ‘what does it take to develop and produce sophisticated car parts?’ It requires a mix of knowledge, intermediate inputs, services, finance, the right people in the right place, and very good co-ordination. Where do these things come from? From all over the place, but mostly the EU.

The Single Market plays a pivotal role in facilitating this process of increasing specialisation, for it encompasses the four freedoms for moving goods, services, capital and people. Hence, a focus on manufacturing alone is too narrow. Trade in services is not only important in its own right but it also constitutes an integral part of the UK’s manufacturing base.

But the salience of services is often underestimated for two reasons.

The first is that some services trade camouflages as merchandise trade, because a good deal of the gross value of merchandise exports consists of embodied services inputs. Estimates put the share of the EU’s gross merchandise exports that actually reflect services content at 35%, or about 300 billion Euro.

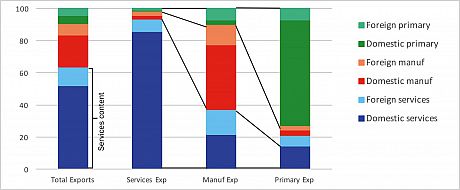

Second, suitable data to trace out how countries add value in terms of both goods and services along supply chain trade has only recently become available. Turns out that for the UK, over 60% of its overall export value in 2011 represented services content (Figure 1, first stacked bar). Most of this is domestic service content (dark blue), but UK manufacturing exports—closer to the car industry example—use domestic and foreign imported services in roughly equal proportions, together nearly 40% of export value (third stacked bar).

Figure 1: Domestic and Foreign Value-Added Contribution to Gross Exports in the UK, percentage shares, 2011

Source: WTO, UK profile “Trade in Value Added and Global Value Chains”; author’s representation.

And the twist is that all these services are only the ones directly traded (and thus leave their mark in the balance of payments). Investment in services sectors as well as people popping around to discharge services in person have not even entered the picture. Arguably, capital and skills are as important but even less visible in the data.

So in a sense, services are hiding in plain sight. Nonetheless services are essential for growth and jobs through the many ways in which they enable economic integration with the EU and other countries. Thus one would hope that services trade, in its many forms, is given due consideration in any future trade deal with the EU post-Brexit.

14 December 2016

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.