Quasi-Bans: enhancing political feasibility while advancing phase-outs

Posted on behalf of: Paola Yanguas Parra and Jochen Markard

Last updated: Monday, 2 February 2026

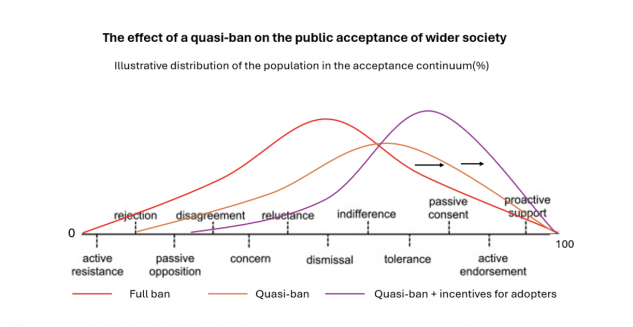

Recent experiences from the Swiss heating sector show that quasi-bans can be an effective tool for accelerating phase-outs while increasing political feasibility. By targeting the majority of actors in the “middle” of the social acceptance continuum, and combining subsidies and other measures to promote alternatives, quasi-bans can help shift decision-making at critical moments.

Climate policy should target the majority in the middle

As a behavioural economics professor once explained in a lecture on deterrence theory: we do not lock our doors for the people who would never break in, or for those who would break in regardless (they will find a way). We lock our doors for the group in the middle: the people whose behaviour depends on the context, the incentives, and the opportunities available to them (See research by Greg Pogarsky 2006 and Hirtenlehner & Leitgöb 2024). .

This insight from behavioural science can also be applied to public policy using the idea of the social acceptance (SA) continuum and actor reorientations . At its core, the continuum moves past binary assessments of acceptance positions (support/rejection) to a more granular scale of positions (e.g., passive opposition, reluctance, tolerance, endorsement, etc.). It can also be used to design policies to primarily target those in the middle.

When thinking about sustainability transition policies, the key issue is not to persuade the minority already deeply committed to climate action, nor the minority that ideologically opposes change. The real leverage lies in shaping the decisions of the majority in the middle: those who will adopt low-carbon solutions if they are affordable, practical, accessible, and socially accepted.

Climate policy, then, is not just about technologies but also about influencing decisions in this middle space. And this is exactly where quasi-bans come into the picture.

Using a spectrum of policies

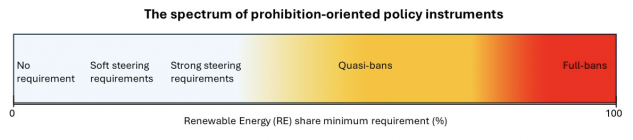

In the debate on phasing out carbon-intensive technologies, bans are often understood as binary: either a technology is, or will be, legally prohibited, or not. But such a black-and-white framing hides a much larger policy toolbox that can be used to influence behaviour across the social acceptance continuum.

Quasi-bans sit between strong incentives (e.g., subsidies, tax benefits) and full bans. They introduce requirements (e.g., minimum renewable energy shares in heating systems or car fuels) that make low-carbon alternatives the default choice, while still allowing for exceptions, flexibility, and local adaptation.

This is crucial because social acceptance is not static. It changes based on how policies are designed, how alternatives are presented, and how burdens and benefits are distributed. Quasi-bans do not force the transition on everybody; but they tilt the playing field in favour of the sustainable option, while ensuring fairness and practicality.

The Swiss case: A laboratory of fossil heating phase-out policy innovation

As we explained in a previous post, Switzerland provides a particularly insightful real-world experiment. Because national-level fossil heating bans faced political and legal challenges, Swiss cantons (regional governments) began designing their own regulations. Over time, this resulted in a spectrum of policy approaches:

- Full bans on installing new oil or gas heating systems (e.g., Basle-City, Zürich, Geneva).

- Quasi-bans, where very high renewable energy shares are required, making fossil heating replacements very unlikely (e.g., Schaffhausen, Fribourg, Valais, Zug)

- Soft steering approaches, with renewable energy minimum shares close to the federal minimum of 10%. (e.g., Grisons,Ticino, Basle-Country, Schwyz)

This variation allows us to observe how different policy designs shape decisions. And the results are noteworthy: across cantons with full bans or quasi-bans, the replacement of fossil heating systems with renewable or waste-heat systems were between 80 and 95%, compared to much lower shares in cantons with soft steering requirements. This is a strong indicator that these approaches are highly effective at accelerating the heating transition.

The Swiss experience also points to the importance of managing political feasibility of the (quasi)bans: all policies were accompanied by exceptions, hardship clauses, transitional timelines, and a clear subsidy support scheme, which are all key features/measures to reduce increase the political feasibility.

When strong regulatory requirements (“sticks”) are softened to ease implementation (e.g. quasi-ban), political feasibility increases. And when they are complemented by financial incentives (“carrots”), the sustainable option becomes more attractive and feasible. This combination represents a powerful example of how policy design can target the majority in the middle of the acceptance continuum.

Acceptance, reorientation, and transition speed

Previously, we have argued that political feasibility is not just a background factor but a central driver of transition speed, highlighting the need for further research on what policy tools and their combinations are most effective in shifting acceptance across different groups. Here, we argue that quasi-bans, when paired with subsidies and supportive measures, are a good example of such a combination for an acceleration strategy. They:

- Reduce dependence on voluntary behaviour change alone, encouraging adoption of clean alternatives before major infrastructure lock-ins occur

- Provide clear, predictable signals to markets, supply chains, and households, while encouraging rapid change, as opposed to soft steering incentives.

- Reduce the risk of backlash associated with rigid bans, which may lead to fierce opposition.

This matters greatly in sectors such as heating and mobility, where individual decisions accumulate into system-wide transformation. Installing a new heating system or buying a new car has repercussions for 10–30 years. Policies that guide decision-making during these key replacement moments are therefore crucial. Quasi-bans can do this without triggering the political opposition that often accompanies full bans.

Moving the Middle

If we want to move from incremental progress to transition acceleration, policy design cannot be only done based on technology performance or economic optimization, but should also account for the social reality of decision-making.

The Swiss experience shows that we are not limited to a binary choice between soft incentives and hard bans. There is a large, underused middle ground: quasi-bans, which can encourage large-scale adoption of renewable alternatives while maintaining implementation flexibility and strengthening political feasibility.

In other words, they help us move the majority in the middle of the acceptance spectrum, who is the group that ultimately determines whether transitions succeed or stall.