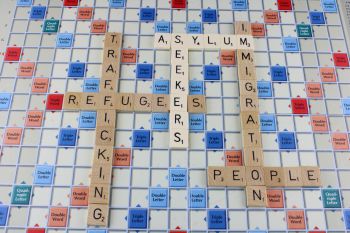

From Hope to Handcuffs: The Criminalisation of Desperation for Asylum Seekers

Posted on behalf of: Kara Paterson, Sussex Law Clinic

Last updated: Wednesday, 4 June 2025

I grew up in small-town Canada; the kind of place where everyone knows everyone and seemingly no one can leave fast enough. That’s why I laughed when I heard about the foreign national arrested at Gatwick Airport for possession of a fraudulent Canadian passport while attempting to reach a place like my hometown. Then it happened twice more and instead of it being something that I could laugh about, it became a concerning pattern.

Having worked with the Lewes Organisation in Support of Refugees and Asylum Seekers as part of my experience in the Criminal Justice Clinic at Sussex University Law School, I was exposed to stories that shattered my small-town worldview. I met foreign national prisoners awaiting deportation as a result of their criminal offences, their stories nothing short of something beyond my wildest imagination, including right-wing dictatorships, forbidden relationships, and the realities of gang culture. This has given me a unique insight and better understanding of why people do the things they do (even if they know they shouldn’t) when backed into a corner.

The cost of living continues to rise yet asylum seekers’ allowance remains stagnant. For a single person, the average cost of living is approximately £1,732/month with rent (£645 without), averaging £161/week for bare necessities. Each week, asylum seekers might receive a measly £49.18 with some receiving only £8.86/week. Living on £8.86, an asylum seeker could buy one Greggs Sausage Roll every day and have precisely £0.11 leftover. Earning less than £95/week constitutes extreme poverty, further exacerbated by asylum seekers lacking the right to work.

Extreme poverty and crime are inextricably connected. In 2024, non-violent crime rates in the most income-deprived areas of London were 41% higher than in wealthier areas. The collectivist approach argues that crime stems from social inequalities, with the most vulnerable at greater risk of criminal behaviour. Higher criminal activity in income-deprived areas is no surprise with low-earning individuals potentially turning to crime to satisfy their needs.

The wave of foreign nationals attempting to reach Canada with forged passports is not an act of inherent deviance but one of sheer desperation as poor asylum support can cause those with no history of criminal activity to commit crimes. The system they believed would protect them failed. Now they face further dehumanisation within an underfunded, overburdened prison system that regards them as little more than a burden on the taxpayers without an adequate fight since asylum seekers are denied legal aid in cases of deportation despite extreme poverty. The heinous truth is that these men are not hardened criminals, they are victims of systemic failure:

- The crying father who hasn’t seen his children in two years is being deported to a dictatorship where he can’t provide them a better future.

- The Orthodox man who was brutally beaten for his relationship with a Muslim woman will be forced back to a country where he might be killed for falling in love.

- The man fleeing forced gang initiation in a second country will now be sent back to the very place he first tried to escape.

The epidemic of forged Canadian passports and forced deportation is a symptom of a greater disease rooted in a lack of resources, support, and a stripping of rights to a fair trial for asylum seekers. These individuals sought safety but were met with indifference and punished for their desperation. I can no longer laugh at their attempts to reach a place like my hometown, a place that awarded me opportunities they never had. The next time I order a Double Double (a staple Canadian coffee order) at my local Tims, I’ll be grateful and allow it to serve as a reminder to continue to fight for a world where others have the same chances I do.