Cancer research unlocks 30-year genetic puzzle

Posted on behalf of: Sussex Genome and Damage Stability Centre

Last updated: Tuesday, 12 June 2012

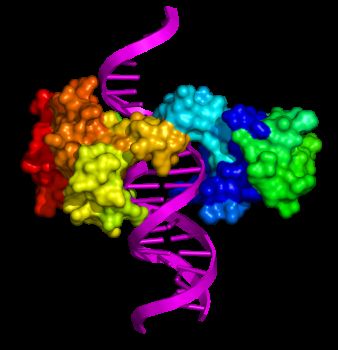

Structure of PARP1 damage recognition module (rainbow coloured) binding to a break in one strand of a DNA double helix.

Sussex scientists have solved a 30-year genetic puzzle that could help enhance treatment for certain types of “inherited” cancers.

The findings relate to an enzyme that plays an important role in the repair of DNA – the genetic blueprint for all life which, in mutated form, leads to the uncontrolled reproduction of cells and the development of cancers.

The enzyme – PARP1 – was first identified as a DNA damage sensor by Professor Sydney Shall in research undertaken at Sussex in the 1980s. Its discovery led to the development of drugs that blocked the DNA repair mechanism in breast, prostate and ovarian cancers found in people who have a family history of those diseases.

But for the past three decades scientists have not known exactly how the enzyme recognised and repaired DNA damage.

A study by the Genome Damage and Stability Centre at Sussex and the Adolf Butenandt Institute, University of Munich has now shown, using structural biology, biochemistry and cell-imaging techniques, that two PARP1 molecules cooperate with each other to detect the DNA damage and then signal to other molecules to bind together at the damage site.

Professor Laurence Pearl, who led the research team with Dr Antony Oliver, says: “Drugs that stop PARP1 from signalling kill a range of breast, ovarian and prostate cancers in people whose tumours have defects in other DNA repair systems, and who often come from families with a strong genetic predisposition to those diseases.

“Now we have a clearer idea of how PARP1 actually recognises damaged DNA and fires off its DNA damage signal, we can target this system with far greater precision.”

The detailed knowledge of how PARP1 signals DNA damage will greatly assist the development of the next generation of drugs that exploit the genetic changes that cause cancers, to kill them, while sparing normal tissues and causing far fewer side-effects.

The team’s findings were published online on Sunday (10 June) in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. Their research was funded by Cancer Research UK.