News

Portraits of Presence: How Sussex Became the Canvas for a Radical Black Archive

By: Bud Johnston

Last updated: Friday, 13 June 2025

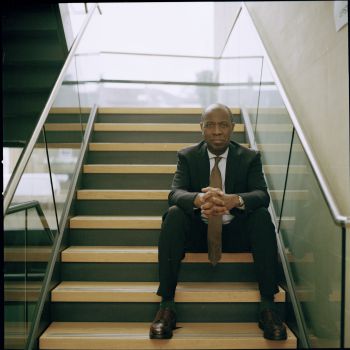

Portrait of Clive by Eddie

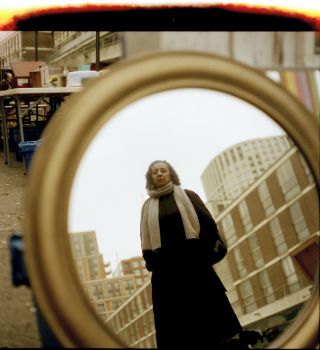

Portrait of Gilane by Eddie

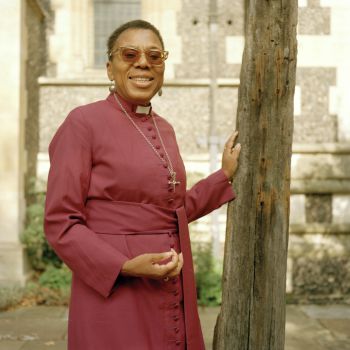

Portrait of Bishop by Eddie

A quiet revolution is unfolding at the University of Sussex—one that isn’t shouted from rooftops but spoken gently through film negatives, vintage cameras, and stories waiting too long to be heard.

Led by acclaimed photographer and archivist Eddie Otchere, alongside legendary photographer Charlie Phillips, a powerful body of work is taking shape that celebrates the contributions, resilience, and intellectual firepower of Black alumni. What began as a single Observer magazine cover featuring filmmaker Steve McQueen has blossomed into a living, evolving portrait series that speaks directly to Black legacy at Sussex.

But this isn’t just about portraits. It’s about presence. “The stories had to be told,” Eddie says. “The optics matter. And this work—this archive—is for us.”

From Pandemic to Portraits

The project's genesis traces back to the pandemic, when Otchere assisted Charlie Phillips on a shoot with Steve McQueen. This encounter reignited Phillips’ passion, drawing him out of semi-retirement and back to the Hasselblad—the square-format vintage camera that defined his golden era. "Charlie’s best work is always with that camera," Eddie recalls. “Once it’s in his hands, the conversation becomes the image.”

After Sussex saw McQueen's portrait on the Observer’s cover, the University reached out. Their timing aligned with their own efforts to honour the legacy of Sussex alumnus Len Garrison, co-founder of the Black Cultural Archives. What followed was a serendipitous alignment of histories—Eddie and Charlie’s personal ties to BCA, Sussex’s archives, and the lives of Black radical thinkers who had passed through the University’s doors.

The Sitters: Mapping a Radical Legacy

The early sitters formed a who’s who of Black British intellectual and cultural figures. Paul Gilroy, whose work shaped generations of thought on race and diaspora, was the first name on the list. "He had to go in first," Eddie said. "He's the foundation."

Each sitter was chosen not simply for accolades, but for the legacy they forged—often quietly—through education, community-building, and resistance. Figures like Michael McMillan shared rich memories of life in Brighton: of cooking with friends, creating cultural space, and finding solace in the 24-hour library that “had no colour bar.” These portraits are accompanied by interviews—oral histories that root the subjects not just in their careers, but in Sussex itself.

The process has grown organically. Departments across the university have advocated for different forms of Black excellence—some championing writers, others calling attention to scientists and doctors working on sickle cell, or tech entrepreneurs quietly transforming their fields. “Each faculty has a different sense of what excellence is,” Otchere said. “Our job is to document all of it.”

A Collaboration Rooted in Care

Otchere’s partnership with Phillips is both technical and deeply human. The pair work in tandem, one talking, the other loading film or adjusting the frame. The method is reminiscent of 1960s Rome, when Phillips worked as a paparazzo in the golden age of cinema. “Charlie’s a social creature,” Eddie laughs, describing old-school tricks to distract celebrities while grabbing the perfect shot.

Even after two strokes, Phillips continues to shoot—his body slowed, but his spirit undiminished. Their sessions have become intergenerational collaborations, with Otchere often mentoring students in the same way Charlie mentored him. “We want students to support Charlie, to learn the process, to witness how a portrait becomes a document.”

Beyond the Frame: Creating a Living Archive

More than 12 portraits have now been created. The first six—known as the “First Contact” exhibition—were displayed on campus, with plans to house the collection in the University library permanently. Each sitter receives prints, with many, including Gilroy, using them for personal projects or public profiles.

The photographs aren’t digital-only. They are processed in a darkroom, printed, annotated, and stored—ensuring they remain accessible without reliance on screens. “We’re not building images for now,” Otchere says. “We’re building for tomorrow.”

With interest from institutions like the National Portrait Gallery and discussions about expanding the project internationally—the scope continues to grow. But for Eddie, the heart of it remains here: “It’s a Black conversation, in a Black space, among Black thinkers.”

What Comes Next

Plans are underway to install the portraits across campus—paired with first-person narratives or even audio clips, allowing visitors to hear the voices of the sitters in their own words. “We’re not just displaying images,” Otchere stresses. “We’re curating presence.”

True to the ethos of Black at Sussex, this initiative is collaborative to its core. Students, staff, and alumni alike are invited to shape how the portraits are seen, shared, and understood. “It has to be open-source,” Eddie insists. “Let’s negotiate. Let’s be transparent. Let’s share the load.”

In a time when the erasure of Black contribution to British history remains a threat, projects like this are urgent acts of preservation. And as Sussex continues to reckon with its own role in those histories, these portraits are not just art—they are testimony.

The Black at Sussex intiative is planning a launch and display event in October 2025 coupled with Eddie providing a guest lecture on the collaboration. Stay tuned in with us to hear first.