Treasures of The Keep

From an original 15th century Caxton-printed version of a Benedictine monk’s chronicle to the electronic submission of hundreds of people’s diaries documenting what they did on 12 May 2021, the University of Sussex’s Special Collections, archived at The Keep, is a varied and wondrous collection.

Housed at The Keep in Falmer, alongside the archives of East Sussex Record Office and Brighton and Hove City Council, exists a collection of documents, pictures, photographs and books pored over by academics, students, writers, researchers and those just curious to explore the past.

“Archives are often the building blocks of original research,” says Richard Wragg, the University’s Special Collections Manager. “As centres of learning, it’s essential that universities develop collections, not only to further our understanding of the past, but to help train the researchers of the future. This fantastic resource means that our students have access to unique and precious collections and can explore them through seminars and independent study.”

There are more than 70 collections in the care of the University. They include the papers of Leonard and Virginia Woolf, personal correspondence of Rudyard Kipling, an archive of German-Jewish life from several different sources, and the much-loved Mass Observation Project: an ongoing collection of personal diaries that has captured the lives of people in Britain since the 1930s.

Among the most recent acquisitions by the University is the archive of the late Jeremy Hutchinson QC, Baron Hutchinson of Lullington, who died in 2017 at the age of 102. He was one of the most high-profile criminal defence barristers of the 20th century and said to be the character inspiration for John Mortimer’s 1970s television series Rumpole of the Bailey.

In a long and celebrated career, Hutchinson’s clients included Christine Keeler, who was tried for perjury during the Profumo affair. He also represented the infamous cannabis smuggler Howard Marks, the art forger Thomas Keating, and the MI6 spy George Blake, who was convicted in 1961 for being a double agent working for the Soviet Union.

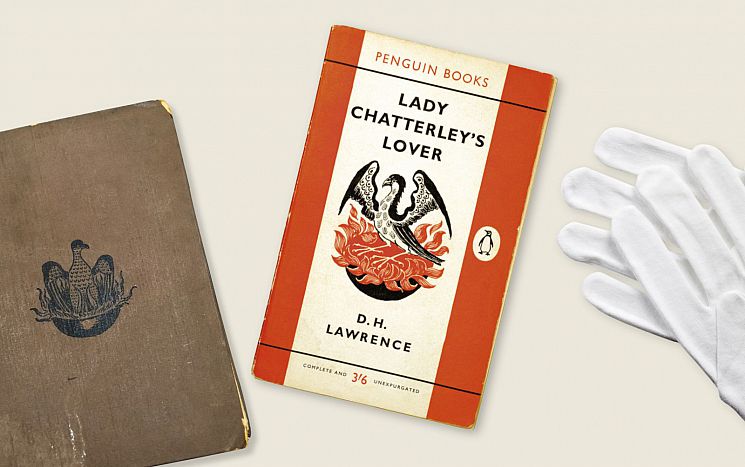

Most notably, Hutchinson was part of the team that successfully defended Penguin Books for publishing D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960. The novel had been printed in France and Italy since 1928 but, because of its preponderance of sexual references and lewd four-letter words, had been banned in England. Hutchinson looked to the support of the literary establishment, including writers such as E. M. Forster and Cecil Day-Lewis, to be witnesses for the defence on the grounds of the novel’s cultural and literary importance. The archive contains a letter to Hutchinson from the poet John Betjeman, who wrote that Lawrence “is earthy but not in the least salacious.”

The acquittal of Penguin Books (by a jury which unusually included three women) not only led to a change in the UK Obscenity Laws but was seen as a watershed moment for literary and sexual liberalism.

The novel went on to sell three million copies in its first year of publication and Hutchinson was hailed a hero. The archive contains an original 1928 copy signed by Lawrence and given to Hutchinson by his mother, Mary, with the inscription: “To Jeremy, in remembrance and honour of the great victory and your part in it. Old Baily October-November 1960.”

“One of the interesting aspects of the Hutchinson archive is that it’s a family collection, with documents and correspondence from all manner of significant figures of the 20th century,” says Richard.

Hutchinson’s father, St John, was also a QC and was, coincidentally, giving D. H. Lawrence advice in 1917 when a selection of Lawrence’s poems was confiscated by the authorities.

Mary Hutchinson was a writer on the fringes of the so-called Bloomsbury Group and known to have had a lengthy affair with Virginia Woolf’s brother-in-law, Clive Bell. The archive contains correspondence with Vanessa and Clive Bell at Charleston, along with T. S. Eliot and Aldous Huxley.

In 1940 Hutchinson, then a Royal Navy officer, married the actress Peggy Ashcroft after introducing himself to her when she was appearing at Theatre Royal Brighton. Peggy had been married twice before and was seven years Jeremy’s senior. The archive includes largely unseen correspondence between Hutchinson and Ashcroft from the war years, during which she wrote about the birth of their daughter, Eliza, detailed her theatre work with the likes of John Gielgud, and hoped for her husband’s safe return from war.

In fact, in 1941, while serving under Lord Mountbatten, Hutchinson was a signals operator on board the destroyer HMS Kelly when it was sunk by a German bomber. He was lucky to survive as half the crew perished. The tragedy is said to have inspired In Which We Serve, the 1942 film drama directed by playwright Noël Coward, who was also a family friend.

The archive has significant overlaps with the University’s existing archives, particularly those related to the Bloomsbury Group, which is invaluable for scholars and researchers looking to piece together the past.

“New acquisitions such as this can further the work of academics near and far,” says Richard. “They also complement our existing collections and, of course, the record of the University of Sussex’s own story. Through them, impactful research takes place.”