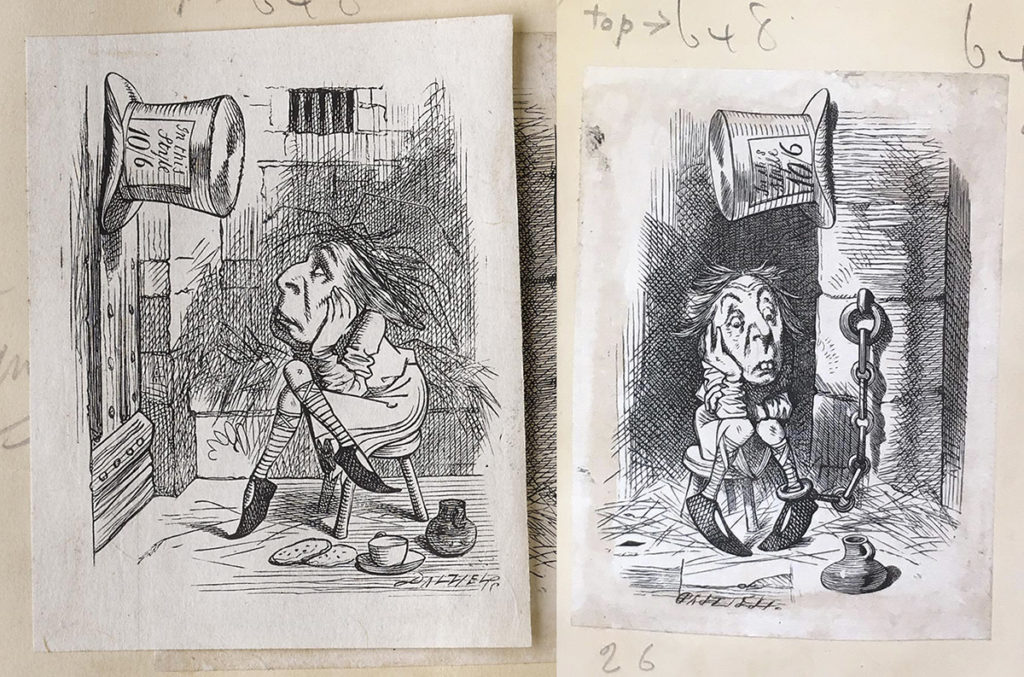

In celebration of the publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in November 1865, we have a special blog post by Nicholas Royle, Professor of English at the University of Sussex. In this piece he responds to the two images below, two different renderings of same illustration, known as ‘Living Backward’, or the ‘Hatter in Prison’. On the left is the first, rejected version. It appears in the album as a flap; if you lift the flap you see the final illustration, pictured on the right. Both these images feature in the Making Prints and Books section of our online exhibition Alice to Alice: Dalziel 1865 – 1871.

The Hatter and the King’s Messenger

What does a picture keep under its hat? Thinking about these two engravings together might detain us at Alice’s leisure for some time. There are fascinating differences between these engravings but they also form a remarkable pair, a kind of twinning or doubling that, more perhaps than any other image in the Alice books, speaks of the Alice books, and tells a story about them and about the archive. Each in its singular manner ‘keeps prisoner its own dream of a world’, in Walter Pater’s phrase, each is locked up, incarcerated, buried alive in its own moment, while also offering itself as a kind of unending pictorial performative. The engraving that doesn’t appear in the book publication of Through the Looking-Glass is, in conventional terms, the rejected image, but both engravings are images of rejection, about rejection, being rejected. In the so-called rejected image the figure looks up as if bereft, yearning, lost, puzzled, at the hat. In the other (what we might call the familiar) image, the figure looks down, also lost and puzzled, and perhaps more skewy-eyed and crazy-looking. In both cases it is the hatter, evidently, and all the madness of the books is encapsulated in this: the King’s Messenger who is ‘in prison, being punished’, as the White Queen puts it in the ‘Wool and Water’ chapter of Through the Looking-Glass, is the Hatter of ‘A Mad Tea-Party’ in the earlier book, Alice in Wonderland. There is a bizarre transference or shuttling of characters between the two books, in an unprecedented kind of adventure underground that takes place across image and text. In the so-called rejected engraving, the sense of a prison is intimated through the bars in the wall above the man’s head. In the more familiar engraving the bars are gone and the more explicit cruelty and brutality of the heavy chain around the man’s left foot is the prison index. In the rejected image the rejected man has the makings of a tea party for one – the biscuits and cup and saucer on the ground beside him. The linkage back to the mad tea-party is more obvious, if no less strange. In the engraving that was published in Lewis Carroll’s book there is no sign of sustenance besides a jug (perhaps of water). What is the hat? What is a hat in a picture? There’s a sinister suggestion, perhaps, of the head that could be under it, as if the image is perpendicular to itself, cutting out, cutting in. There is weird hatching, hatching weirdness, in both works. In the so-called rejected version, it’s as if the composition of the figure of the composite figure of Hatter and King’s Messenger were tearing its hair out or having it cut, hair falling out, joining the hatching work of the wall behind him. In both engravings there are five feet – the three feet of the stool and the two, of the hatter, tip-toe, daintily crossed or pointing in to one another. Together they figure, each in a singular manner, the revolutionary idea of living backwards. To recall the Queen’s words: ‘That’s the effect of living backwards… [T]here’s the King’s Messenger. He’s in prison now, being punished: and the trial doesn’t even begin till next Wednesday: and of course the crime comes last of all.’ With the hat (‘In this style 10/6’) and with the recognizableness of the Hatter (more pronounced and therefore perhaps preferred in the originally published engraving), this double-picture opens up a cryptic new path or passageway between the books, concerning the thought of novels and pictures as embodiments of living backwards.