Exhibition Intro ~ Map ~ Next Section

Click a thumbnail to enter the gallery. Use the arrows at either side of the image to skip forward or back.

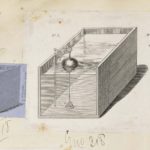

The images in this section are fascinated with small architectural details and their potential for fantastical embellishment, particularly image 15 from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and image 16 from John Taylor’s catalogue of Cast Iron Rainwater Goods (see gallery above).

Applied arts and design rose to new prominence in Victorian Britain. One illustration after Arthur Hughes of an angel weaving (no. 13) shows some of the idealism behind this movement. In 1851, the Great Exhibition in South Kensington had brought together decorative arts objects from all over the world – from vases and metalwork, to textiles, furniture and carriages. People flocked to see it, and Dalziel engraved around 785 illustrations for the official catalogue published by The Art Journal. Following the Great Exhibition, South Kensington became the site of the Victoria and Albert Museum, with collections specifically intended to inspire designers, including those at the affiliated Schools of Art. Indeed, the 1871 census shows that in the same year Through the Looking Glass was published, Edward Dalziel’s son Gilbert was an art student in South Kensington. He would later join the firm Dalziel Brothers. The stunning wood engraving of an Indian column that is included in this section (no. 17) is the kind of image he and his fellow students might have closely examined.

Throughout the century, Dalziel engraved copious images in the field of design, from cast iron stoves for Coalbrookdale, to fashion and furniture for Liberty’s department store. This section presents some made between 1865 and 1871. The first six images focus on the domestic interior. The iconic image of Alice in an armchair is paired with another after Arthur Boyd Houghton of a woman disappearing in luxurious upholstery. An illustration for Ellen Wood’s novel Anne Hereford (no. 3) includes a fashionable Japanese-style screen, highlighting the modernity of the room. Then we have three rather different takes on domestic interiors: a design for a kettle (no. 4), a door handle (no. 5), and designs for a toilet (no. 6), advertised as ‘Death in the Cistern, Bishop’s Patent Camden Sanitary Valve, for preventing the contamination of water by sewer gases’.

Following this, images seven to twelve present an unusual view of toys, shown as objects of commerce and design, rather than sentimental play. Alice’s sheep shop (no. 7) is paired with a bleak toy shop illustration after Arthur Hughes (no. 8). The dolls look like wrapped corpses. Then there are two wood engravings illustrating the same scene from Charles Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, one for the first edition, after Marcus Stone (no. 9), and one for a reprint, after Arthur Boyd Houghton (no. 10). These show Jenny Wren, a child forced into premature financial maturity. Instead of playing with dolls’ clothes, she creates them for money. Once again, following these illustrations we consider the design behind them; the eleventh and twelfth wood engravings offer patterns for making dolls and dolls’ clothes.

Bethan Stevens

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for 'Looking-Glass House', in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/DN2-28_p152.jpg-detail-2-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for 'Wool and Water', in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/DN7-28_p152.jpg-detail-3-150x150.jpg)

![Dalziel after John Tenniel, illustration for 'The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill', in Lewis Carroll [Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland](http://www.sussex.ac.uk/english/dalziel/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/DN15-20_p134.jpg-detail-150x150.jpg)