Carey Gibbons recently completed a Ph.D. from the Courtauld Institute of Art: The Limits of the Body in Victorian Illustration: Arthur Hughes and Frederick Sandys. Gibbons’s research crosses disciplines, engaging with the illustrations of Hughes and Sandys in relation to their accompanying texts and Victorian science, religion, and gender constructions. She recently curated an exhibition at the Columbia University Rare Book & Manuscript Library on the illustrations of Arthur Rackham and currently works in the Drawings, Prints, and Graphic Design Department at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

An aspect of my research that continually fascinates me is the interplay between a growing materialism during the Victorian period and the corresponding interest in the immaterial, expressed in debates relating to topics such as the ether, spiritualism, and the unconscious mind. I am specifically interested in how these seemingly contradictory developments relate to conceptions of the human body and are reflected through the medium of Victorian illustration. My research has focused on Arthur Hughes and Frederick Sandys, two Victorian illustrators who have received little attention but took full advantage of the possibilities of wood-engraved illustration, using the medium to explore new ways of thinking about identity, subjectivity, and bodily representation.

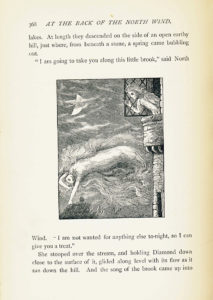

My Ph.D. thesis explores the various ways in which Hughes conceives of the body in terms of its elusiveness and indeterminacy. For example, in this illustration from George MacDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind (1871),engraved by the Dalziel Brothers, the female personification of the North Wind is depicted falling backwards, with the curves of her arms, legs, and face filling the air and suggesting both fluidity and flexibility (Figure 1). Her wavy strands define both the air and her hair, while the ripples of clouds resemble the wavy strands, further blurring the boundaries between the body and the natural world. The illustration can be interpreted within the context of the work of Victorian meteorologists, who characterised the air by referencing waves and describing it in both liquid and gas terms, drawing attention to its fluidity and elasticity. The illustration can also be viewed in relation to Victorian understandings of light and electromagnetic radiation in terms of the propagation of waves that rippled within the ether—an elusive and subtle yet universal medium for the transmission of vibratory motions through which atoms, molecules, stars, and planets passed. In Hughes’s illustration the form and substance of the female body is not completely fixed or static, suggesting the variable and intangible nature of corporeal experience.

An intriguing contrast exists between Hughes’s interest in the elusive or indeterminate and the medium of wood engraving through which his illustrations were reproduced. Wood engraving stresses a linear conception of the world, emphasizing the power of each individual line and implying volition and a firmness of the hand. The reproductive technique would have involved cutting away the parts surrounding the lines drawn by the artist, carefully separating one part from another and defining each line with the pressure of the graver. Although Hughes’s illustrations are reproduced through this medium, which appears to stress the materiality of bodies and structures through its emphasis on delineation and firm boundaries, they cultivate a sense of mystery and unpredictability.

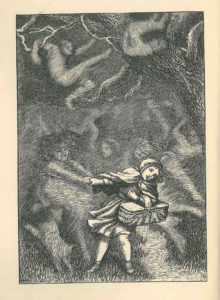

Christina Rossetti’s Speaking Likenesses (1874) similarly provided Hughes with the opportunity to examine the body in terms of its changing form and properties (Figure 2). When Maggie, the orphan granddaughter of a shop owner, offers to take the forgotten parcels of two girls a long distance through the wood to their house at night, she comes across a group of wild, grasshopper-like children spinning, wrestling, and darting with animal energy. A hazy, indistinct region surrounds Maggie. The texture and substance of the air oscillates between solid and less substantial matter, and forms appear only to vanish in the wood. The children appear to exist somewhere between the seen and the unseen, resisting categorisation; form and gender are uncertain.

Hughes’s illustration for the story presents Maggie as a Little Red Riding Hood-like figure and explores the clash between good and evil, alluding to a borderland where boundaries are contested and negotiated. Hughes explores the ongoing struggle between the controlling, restraining power of the Will and one’s automatic or emotional impulses throughout Speaking Likenesses, and in this illustration, he makes it deliberately unclear whether Maggie or the wild children are in charge. Although Maggie appears to be pulling herself away from the shadowy figure grabbing her hand, her serene facial expression does not suggest complete resistance or control. The boundaries of the body are presented as open and unstable; Hughes suggests that Maggie’s body might be pulled into the shadowy wood, causing her to lose her materiality and become more undefined in appearance and substance.

These are only two examples from Hughes’s long and prolific career as an illustrator; he produced over 800 illustrations for books and periodicals. After studying his career as an illustrator through my research, I have continually observed his delight in the potential for bodies to be unstable and ambiguous. Paradoxically, Hughes explored metaphors of indeterminacy and mutability repeatedly through wood-engraved illustration, a medium that required firmness of thought and hand, stressing the need for an unequivocal, assured line. The work of Hughes encourages us to examine the interplay between materiality and immateriality within Victorian illustration, while inspiring us to reflect on the countless ways that Victorian illustrators envisaged and represented the body.