Michael John Goodman completed his PhD in English Literature at Cardiff University in December 2016. His thesis, ‘Illustrating Shakespeare: Practice, Theory and the Digital Humanities’ explored how digital technology can be used to make sense of historical (specifically Victorian) illustrations of Shakespeare’s plays. The project saw the launch of the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive, an online open access resource that contains over 3000 illustrations taken from Victorian editions of Shakespeare’s plays. In this post, Michael explains the motivation and process behind the archive, and reflects on the future of illustration studies in the digital age.

The Past inside the Present: The Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive

The Past inside the Present: The Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive

What comes to mind when you think of Shakespeare? The latest Kenneth Branagh film, perhaps? Struggling to make sense of the language in school? Merry Englande, ruffs and a good dose of ‘hey nonny nonny’? If we could somehow ask this question to a Victorian, there is a good chance that they would answer: ‘illustrations’.

The Victorian era was the ‘Golden Age’ for Shakespeare illustration. Between 1839 and the end of the century thousands of illustrations were produced within many different editions of Shakespeare’s Complete Works. New printing technologies meant that books could be produced on a mass commercial scale and illustrated books, for the first time, became affordable to working and middle class families. What is so fascinating about these illustrated Shakespeare editions, which were hugely popular in the Victorian era, is that they form a significant part of our cultural heritage and, indeed, our construction of Shakespeare’s plays as we understand them today. Unfortunately, these illustrations are often hidden away in rare books libraries, meaning that they are often inaccessible to members of the general public.

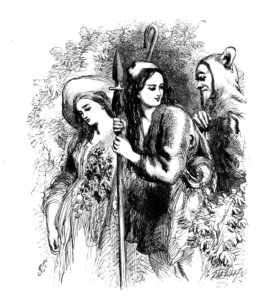

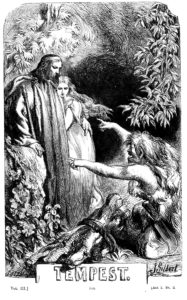

My project, The Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive seeks to rectify this. It is an online, open access resource which contains over 3000 of these Victorian illustrations and it is centred on the four most significant Victorian editions and illustrators of Shakespeare’s Complete Works: Charles Knight, Kenny Meadows, John Gilbert and H.C. Selous. The archive came about when I was exploring ideas for my PhD in English Literature at Cardiff University. Initially the project was just going to be concerned with analysing how Victorian illustrators depicted Shakespeare’s plays. However, as my research progressed, it slowly became apparent that here was a remarkable under-explored and under-appreciated treasure trove of fantastic, curious, and often unnerving illustrations that deserved to be shared with not just academics but also the wider public. The illustrations shown here, by John Gilbert (whose images were engraved by the Dalziel Brothers), for example, are a perfect example of the richness of material available in the archive.

My project, The Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive seeks to rectify this. It is an online, open access resource which contains over 3000 of these Victorian illustrations and it is centred on the four most significant Victorian editions and illustrators of Shakespeare’s Complete Works: Charles Knight, Kenny Meadows, John Gilbert and H.C. Selous. The archive came about when I was exploring ideas for my PhD in English Literature at Cardiff University. Initially the project was just going to be concerned with analysing how Victorian illustrators depicted Shakespeare’s plays. However, as my research progressed, it slowly became apparent that here was a remarkable under-explored and under-appreciated treasure trove of fantastic, curious, and often unnerving illustrations that deserved to be shared with not just academics but also the wider public. The illustrations shown here, by John Gilbert (whose images were engraved by the Dalziel Brothers), for example, are a perfect example of the richness of material available in the archive.

Fortunately, digital technology allows us to reach audiences in a way that is unprecedented. Digital archives allow us to recover hidden histories, celebrate forgotten voices, to enhance our understanding of bygone eras, and to disseminate cultural artefacts in an engaging and innovative fashion. It was with these ideas in mind – about what can be achieved using the digital – I decided to create The Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive.

This was, of course, a large undertaking. Each of these editions contain hundreds of illustrations which would require scanning into the computer, alongside being given the appropriate bibliographical and iconographical meta data (basically, the details about where the image came from and what the image contains), so that the illustrations would then be searchable within the archive. Furthermore, I wanted the archive to be as user-friendly as possible, with a strong focus on design, and to incorporate the ability to use social media so that users could comment upon and share the images on Facebook and Twitter. After four years of working on the project, I launched the archive late last year and the reaction it has received has been hugely positive. In January 2017, Digital Arts Magazine named the archive as one of the top nine on the web for free historical images. Open Culture, Lit Hub, and Fine Books Magazine, amongst others, have also written about the project. As kind and generous as these reactions have been, what I take most from them is that there is a real desire amongst the public to engage with both cultural history and academic research when they have access to it.

This was, of course, a large undertaking. Each of these editions contain hundreds of illustrations which would require scanning into the computer, alongside being given the appropriate bibliographical and iconographical meta data (basically, the details about where the image came from and what the image contains), so that the illustrations would then be searchable within the archive. Furthermore, I wanted the archive to be as user-friendly as possible, with a strong focus on design, and to incorporate the ability to use social media so that users could comment upon and share the images on Facebook and Twitter. After four years of working on the project, I launched the archive late last year and the reaction it has received has been hugely positive. In January 2017, Digital Arts Magazine named the archive as one of the top nine on the web for free historical images. Open Culture, Lit Hub, and Fine Books Magazine, amongst others, have also written about the project. As kind and generous as these reactions have been, what I take most from them is that there is a real desire amongst the public to engage with both cultural history and academic research when they have access to it.

Digital archives are a new medium for producing knowledge. Not only do they allow new research questions to be asked of their content (Victorian Shakespeare illustrations, for example), but their very creation allows us to gain new insights into books, materials, and digital cultures. For example, handling and digitising the illustrated Victorian Shakespeare editions day after day meant that I became acutely aware of how devices such as illustration, the placement of the text within the page and the texture of the paper construct meaning. As Jerome McGann notes, the digitisation process allows us to engage directly and in a very practical way with primary material. Moreover, working with hypertext opens up new ‘interpretive opportunities’ where we are able to see new connections and interesting juxtapositions. It allows images that have been separated by both time and space to be brought together to generate new meanings.

Ultimately, I hope the archive will be used in education to help students of all ages to better understand Shakespeare’s plays and by researchers interested in the Victorian period. However, the archive is available for anyone to use in whatever way they wish. Moreover, I would like to inspire other people to have the confidence to make similar archives and to recognise that with curiosity, imagination and creativity we can make scholarship exciting, interesting and available to all. We now live in world where, thanks to technology, we can begin to share our cultural history not just with a privileged few but everyone. The process of creating a digital archive is a way of exploring the past whilst actively constructing research for the future.

~

You can learn more about the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive in an interview Michael did with arts and culture website, Hyperallergic and in this short video about the project made in collaboration with the BBC.

You can also follow the Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive project on Instagram.