Lindsay Smith is Professor of English and co-director of the Centre for Photography and Visual Culture at the University of Sussex. She has written extensively on Victorian painting, poetry and photography, and her work continues to engage the difficult and hesitant spaces between established disciplines. Lindsay’s most recent project is on Lewis Carroll as a creator and collector of photographs, titled Lewis Carroll: Photography on the Move. It is out now from Reaktion Books. Here she responds to two Dalziel wood engravings in the ‘Spectatorship / Reflection’ section of the exhibition.

Ink and Light

I’ve been thinking about ‘medium,’ and about the ‘graphy’ and the ‘photos’ that combine in the word photography, a term coined by Sir John Herschel, eminent scientist and subject of one of the Dalziels’ wood engravings. I’ve been thinking about the writing and the light, that is, or rather the physical mark making of wood engraving and the physical imprinting on a surface by light to produce a photograph (Fox Talbot called his first attempts at photography photo-genic drawings). I’ve been thinking, too, about the wood engraver’s ink in its relation to the physical action of the sun’s blackening of a light sensitized surface. For, to make a photograph is not simply to harness light, of course, but it is also to stop the action of light from running to blackness. Not surprising then that early commentators call light at times too quick; at others a laggard.

When the Dalziels produce images after photographs, in what ways may the manual form of the wood engraving, cut by a dexterous hand, be said to translate, render or approximate an image imprinted (or stained) by light upon a smooth surface? What happens to the causal connection of a photograph to its referent, as facilitated by light, when the photographic image becomes a wood engraving? By extension, how might early conceptualizations of the agency of photography as light’s ‘brush’ or the ‘solar pencil’, attach to a wood engraving of a photograph or one that pictures the medium of photography? These are big questions; and they are ones posed in fascinating ways by the Dalziels’ conjunction of the manual medium of wood engraving and the mechanical one of photography; each possessing an incredible reproductive capacity and an affinity for fine detail.

I want to ponder two images from 1867.

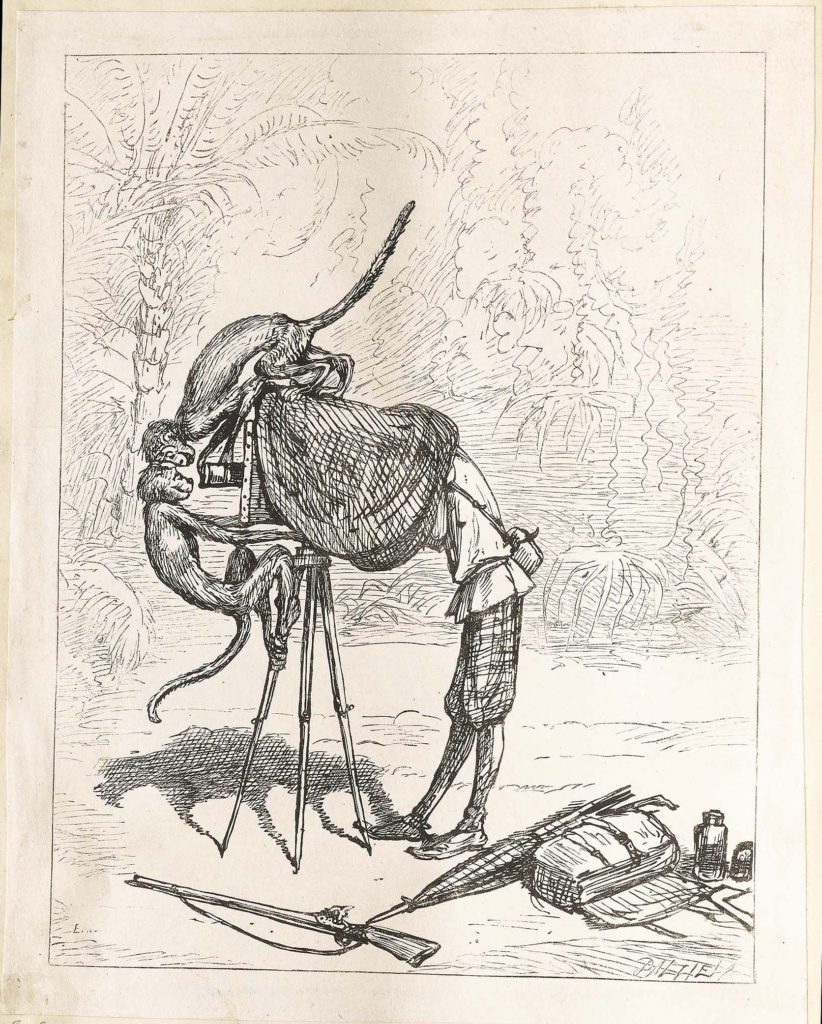

The first is one of many images from the Dalziel albums that represent the apparatus of photography and a range of optical instruments along with the trials of the photographer. It shows a photographer in the field, a rather hazy field but a foreign one we may infer from the faint but unmistakable lines of a palm tree. We encounter the familiar bulky shape of the bulky camera on its tripod. Its hooded operator is in the process of being hoodwinked by fellow primates. As they intercept his lens, instead of the view framed, the faces of two monkeys will meet the photographer’s eyes. Apparently curious to explore the apparatus, they are in the process of ensuring their portraits will imprinted on its highly sensitized plate. If that is, they remain still long enough, and the one monkey removes his paw from the lens.

Griset’s Grotesques was a popular Christmas book. Combining humorous letterpress with satirical illustrations of animals and birds that Griset spent his life drawing at London Zoo, it was aimed at a middle class family readership.

In this image that appeared alongside the title page, Griset presents a striking encounter with photography and a fascinating take upon what had become, by the mid-nineteenth century, the comical figure of the photographer with his cumbersome apparatus. The image also provides an interesting spin on Baudelaire’s much quoted denunciation of a medium so irredeemably attached to realism, and forgetful of the dream, that it inspired a vain public to rush ‘Narcissus-like’ to seek their faces upon polished metal plates. Here, in a pursuit of selfies before their time, monkeys intercept the take. Moreover, the photographic image that usually appears inverted to the photographer as he takes it, will have been oddly turned the right way by the monkey business of hanging upside down. In a multi-faceted joke – about evolution, self-portraiture – Griset withholds the photographic result of this early example of wildlife photography just as it withholds the face of the photographer. Indeed, the photographer/hunter, with his gun, sunshade and bottles of chemicals laid idly by, must neglect to look directly at the scene he wishes to picture in order to capture an image of it. In protecting his highly sensitive plate from the light his work is open to sabotage.

Through comic means Griset’s image reminds us of the dominance of the portrait in early photography. In calls up Charles Darwin’s use of photographs in On the Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals of 1872. The photographed emotions Darwin used were staged ones. Actors held poses of jealously, grief, disgust, for example, for the camera. Yet since photographic images were very expensive the majority of the portrait illustrations in the book were wood engravings after photographs. In a different and vital regard, however, the interception of the camera in Griset’s image also highlights the relative agency of the photographer.

My second image, is a wood engraving of the scientist Sir John Herschel made in 1871 by the Dalziels after a photograph of 1867 by the pioneering nineteenth century photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. Herschel directs his eyes off-frame; incredible transparency substitutes for their blueness. The highly lit contours of his face – frown lines, bags under his eyes and his dazzlingly white hair – emerge from darkness at the centre of the picture. In a wish to mask modernity, Cameron has draped her sitter in dark velvet. Only a white sliver of Herschel’s contemporary 19th century dress visible around his neck has escaped cover. This scrap of white joins the hair around his forehead, stopped as it appears by the velvet hat he wears. It joins the eyebrows to accentuate a bleached patch of emulsion on the top part of the brow itself. Materialised on the plate is Cameron’s desire to capture areas in the visual field that defy the recommended focal length for a portrait image of this type.

I argued a long time ago that, in making a conscious decision not to focus her photographs, and accused of myopia and incompetence by some critics as a result, Cameron was intervening politically in early accounts of the medium that placed a premium upon focus and a high level of clarity. And the issue of focus, or Cameron’s wish to question a notion of focus as the signature of photography, becomes newly resonant when we consider the Dalziels’ version of Cameron’s Herschel.

What happens, I want to ask, when the image migrates from the smooth surface of emulsion, migrates through the intermediate graphic form of drawing and reversal – incised as it into a woodblock – to be laterally restored in its engraved form? Cameron took this photograph of Herschel with her new large format camera with a plate size of 15x 12. She inscribed her portraits ‘taken from life’. In taking them from life she meant she had not enlarged them, tampered with them. The heads she took were life size and the resulting positive on albumen paper that we see was made from a glass wet collodion negative of the same dimensions.

There are many obvious formal differences between the Cameron Herschel and the Dalziel Herschel. The image is reduced in size. The altered angle of the head, the proportions of the chin, the lines on the forehead anticipate Darwin’s use of wood engravings made after photographs in The Expressions. For the wood engraver to realise the graphic elements of the photographic portrait, to cut lines in the hard endgrain of the boxwood block, is to lose, to some extent those places of intense white, where form is bleached out. Yet, by sustaining a vortex at the dark centre of the image, the wood engraving recognizes not only light as the sovereign agent of photography but also Cameron’s idiosyncratic use of it. The fast sun, light’s propensity to run to absolute blackness, is checked, so to speak, by the intermediate tones of the engraver’s ink.

As an absent hand distinguishes a photograph from a wood engraving, the Dalziels recognise the role of light in generating the fugitive photographic image. In the wood engraving of Herschel lines behave in a way that gestures towards Cameron’s approach to her subject. And those lines approximating the agency of photography result in similarly fugitive marks. In so doing, for me the Dalziels’ wood engraving recalls Lewis Carroll’s wonderful conceit, in a letter to a child, about ink that needs no pen; an ink that simply goes by itself.

Lindsay Smith

Image Credits:

Fig 1: Dalziel after Ernest Griset, frontispiece to Griset’s Grotesques; or, Jokes Drawn on Wood, with Rhymes by Tom Hood (London: Routledge, 1867). Dalziel Archive Vol. XXI (1866), British Museum reg. no. 1913,0415.182, print no. 1029. By Permission of the Trustees of The British Museum. All Rights Reserved © Sylph Editions, 2016

Fig 2: Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879), Sir John Herschel, April 1867, albumen print from 15 x 12 inch wet collodion glass negative. Copyright: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2016. All Rights Reserved.

Fig 3: Dalziel after Julia Margaret Cameron (intermediary drawing made by William Rice Buckman), ‘Herschel’, illustration for the magazine Good Words (1871). Dalziel Archive Vol. XXIX (1871-74), British Museum reg. no. 1913,0415.190, print no. 361. By Permission of the Trustees of The British Museum. All Rights Reserved © Sylph Editions, 2016