How Lord Attenborough brought a touch of glamour to Sussex

By: Jacqui Bealing

Last updated: Thursday, 18 May 2023

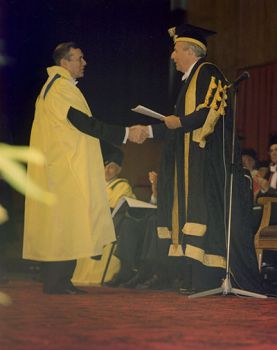

Dirk Bogarde receives Hon D Litt at University of Sussex graduation

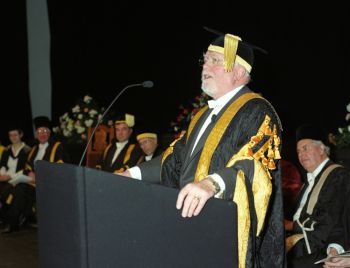

Lord Attenborough gives his first speech as Chancellor of the University of Sussex.

The vast archive of Lord Attenborough’s personal and work papers, looked after by the University of Sussex at The Keep and now open to the public, contains many precious documents that chart the actor and film director’s much-cherished association with the University.

From the late 1960s until his death in 2014, actor and film director Lord (Richard) Attenborough enjoyed a close association with the University of Sussex.

For the University he brought the glamour and excitement of the entertainment industry, albeit with a social conscience. In turn, Attenborough’s roles at the University, first as Pro-Chancellor, and then as Chancellor, satisfied his yearning to be involved in academia.

It was while filming Oh! What a Lovely War in Brighton, in 1968, that Attenborough first forged a relationship with the University. He approached the then Vice-Chancellor, the late Lord (Asa) Briggs, to see if he could spare a few students for some of the crowd scenes on the West Pier and the Downs.

Lord Briggs was happy to oblige in sourcing “cannon fodder”. In an interview before his death, Lord Briggs admitted that Attenborough was always “Darling Dickie” to him from that moment on.

Attenborough’s formal connection with the University of Sussex began in 1970, when he was appointed Pro Vice-Chancellor. His son, Michael, was already an undergraduate in English, and his daughter, Susan, was also soon to take up a place to study Sociology.

His warmth and humour at graduation set the tone for the lively celebrations that have continued ever since, not least because he was frequently joined on the stage by the greats of the film and theatre world, who were receiving honorary degrees.

In 1972 he presented his dear friend, the flamboyant playwright Noel Coward, for the honorary award, Doctor of Letters.

In his speech, he said: “I know of no man who so generously welcomes and encourages the emergence of new talent more than he, and those of us who have had the privilege of singing his songs and speaking his words are forever in his debt.”

A photograph in the archives shows Richard and Michael (who was graduating that year) sharing a joke with Coward, who was Michael’s godfather. Although he remembered to send cards every year to his godson, Michael remembers that Coward could not resist quipping: “Dear boy, haven’t seen you since the font.”

Three years later, Attenborough presented British film producer Michael Balcon (the man behind the Ealing Comedies Kind Hearts and Coronets and Passport to Pimlico, and classics such as The 39 Steps) with an honorary degree, saying of him: “Like all outstanding men he has contributed so much more to the particular field of activity in which he was involved than he could ever possibly have derived from it…”

When Lord Olivier was similarly lauded in 1978, Attenborough made reference to his personal qualities as well as his towering theatrical achievements. “He is a friend of burning loyalty and a man devoid of all false conceit. Superlatives are so often proclaimed with irresponsible ease but in this particular case none will dispute that the man we honour today may in truth be dubbed a genius.”

He went on to joke that, while Lord Olivier was a Brighton resident at the time (living in a Regency house on the seafront), his major flaw was that “…he failed to have the good sense to enter this world some ten miles to the south for, had he done so, Sussex could claim not only his present residence but also his birth.”

The same personal warmth was shown to the actor Sir Dirk Bogarde in 1993. Attenborough mentioned in his speech that he and his wife, Sheila Sim, had known Bogarde since the late 1940s, when they were starlets in acting, and that among their treasured possessions was a picture of their home in France painted by Bogarde’s father.

He went on to comment that, while Bogarde had an outstanding acting career, by the 1990s he had turned his back on that world to write his memoirs, beginning with his childhood in Newick, East Sussex.

“There is no question that his fascinating attention to detail and his ability to conjure character and atmosphere places him among the distinguished writers of our time,” said Attenborough. “Indeed, he wrote to me recently saying ‘mine is a literary world now and my books my life and passion’.

“I personally hope that despite his protestations, before too long, we may again welcome ‘This orderly man’ back to the cinema for our delight.”

In his role as Chancellor, Attenborough attended many other formal University events. The archive contains 32 prompt sequences on small pieces of card that he wrote for a Sussex professorial banquet speech in 1997.

The quirky aide-memoires give an insight into what the speech was about. For example: ‘Typecast – Evil little spivs or quivering psychopaths’ would have been a reference to his chilling performances in the films Brighton Rock and 10 Rillington Place.

Another prompt, ‘Guinea Pig – bald patch – Sheila’, suggests an anecdote about the first movie he and his wife appeared in together in which, as a 25-year-old with hair loss, he played a rebellious 14-year-old schoolboy.

For his inauguration as the University’s Chancellor in 1998, Attenborough gave his most personal speech, revealing the commitment and passion he felt for his new role.

“I am a graduate of what is kindly known as the University of Life,” he said. “In common I suspect with many others in the same position, my lack of university education is something I profoundly regret. And because of my family background, that enduring regret is tinged with not a little shame.”

He went on to explain that his grandfather, Samuel Clegg, was one of the founders of secondary schooling in this country, his maternal uncle, Sir Alec Clegg, was chief education officer for the West Riding of Yorkshire and his father was a fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge and became Principal of Leicester University College.

While both his brothers, David and John, went to university, he chose to take up a scholarship at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

“Yet the fact that I never went to university haunts me,” he said. “And for that reason alone, I do confess that, were my father alive today and here to see me installed as Chancellor of the University of Sussex, it would please me more than I can say.

“He, however, remembering my somewhat slender academic achievements, would I am sure find it absolutely hilarious.”