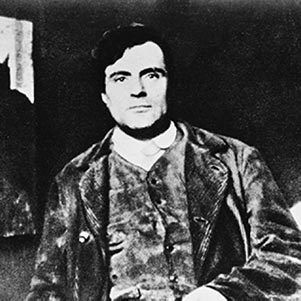

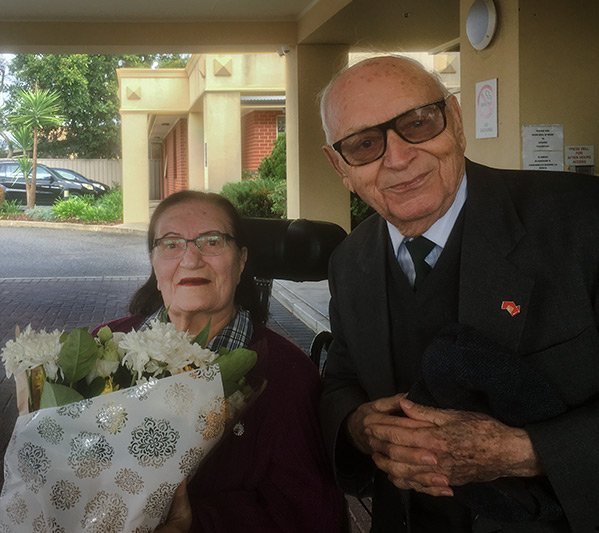

Giovanni Carsaniga (1934-2016)

Nerida Newbigin University of Sydney

Emeritus Professor Giovanni Carsaniga, well known to many Italianists in Australia and abroad, has died in London on 27 March 2016 at the age of 82. Most recently he held the chair of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney from 1990 to 2000, the third holder of the chair which had been established in 1963 and held by Frederick May from December 1963 to January 1976 and by Gino Lorenzo Rizzo from 1977 to 1987. He had previously held the Vaccari Foundation Chair of Italian Studies at La Trobe University from 1982 to 1989 and been been the Visiting Professor of Italian at the University of Western Australia for two years from 1975 to 1977. His earlier academic career had been spent in the United Kingdom, progressing through junior positions at the Universities of Aberdeen, Cambridge and Birmingham, before joining the University of Sussex in 1966, where he rose to the position of Reader. He was elected to a fellowship of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 1989, and appointed Cavaliere Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana

in 1999.

Carsaniga’s appointment to the University of Sydney came at a difficult moment for the department and for the teaching of languages in general. Financial stringency in Italy had the sudden effect of reducing Italian Government support for the Frederick May Foundation for Italian Studies which had been established by Silvio Trambaiolo and carried forward with great enthusiasm by Gino Rizzo; and changes within the University in response to federal government legislation and funding models meant that language departments were quite suddenly subjected to severe cuts. Carsaniga provided leadership and support for staff and students in this period and, with art historian Lou Klepac as chair, continued for as long as was possible the work of the May Foundation.

Emeritus Professor Giovanni Carsaniga, well known to many Italianists in Australia and abroad, has died in London on 27 March 2016 at the age of 82. Most recently he held the chair of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney from 1990 to 2000, the third holder of the chair which had been established in 1963 and held by Frederick May from December 1963 to January 1976 and by Gino Lorenzo Rizzo from 1977 to 1987. He had previously held the Vaccari Foundation Chair of Italian Studies at La Trobe University from 1982 to 1989 and been been the Visiting Professor of Italian at the University of Western Australia for two years from 1975 to 1977. His earlier academic career had been spent in the United Kingdom, progressing through junior positions at the Universities of Aberdeen, Cambridge and Birmingham, before joining the University of Sussex in 1966, where he rose to the position of Reader. He was elected to a fellowship of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 1989, and appointed Cavaliere Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana

in 1999.

Carsaniga’s appointment to the University of Sydney came at a difficult moment for the department and for the teaching of languages in general. Financial stringency in Italy had the sudden effect of reducing Italian Government support for the Frederick May Foundation for Italian Studies which had been established by Silvio Trambaiolo and carried forward with great enthusiasm by Gino Rizzo; and changes within the University in response to federal government legislation and funding models meant that language departments were quite suddenly subjected to severe cuts. Carsaniga provided leadership and support for staff and students in this period and, with art historian Lou Klepac as chair, continued for as long as was possible the work of the May Foundation.

Carsaniga’s curriculum was particularly suited to our needs. For his degree in Lettere at the University of Pisa he completed his ‘tesi di laurea’ with Luigi Russo – these were the days when an undergraduate thesis was comparable with an MA Hons and there was no doctoral degree – on the sixteenth-century writer of short stories Matteo Bandello. His ‘diploma di licenza’ from the Scuola Normale Superiore was in comparative literature with Giuliano Pellegrini, with a dissertation on John Ford’s The Broken Heart. His fellow ‘Normalisti’ included Giulio Lepschy, Carlo Sgorlon, Carlo Rubbia (Nobel Prize for Physics), and Dino Bressan. Immediately after graduation in 1956, he received a British Council grant to study in Britain, and his subsequent academic career was in the English-speaking world.

Carsaniga’s writing followed three strands that wove in and out of each other: literature, philosophy and language pedagogy. His publications included books and articles on Dante, Leopardi, Manzoni, Romanticism and Realism, as well as a very successful general history of Italian Literature, written for translation into German, Geschichte der italienischen Literatur: von der Renaissance bis zur Gegenwart (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer 1970), and the chapter on Romanticism for The Cambridge History of Italian Literature (1996, 1997, now on-line). He also published essays in Belfagor on moral and political questions and throughout his life was an inveterate writer of letters to the newspapers.

Leopardi’s interest in literature and philosophy and science helped to shape Carsaniga’s own thinking about the inadequacy of C.P. Snow’s dichotomy between the Two Cultures, scientific and humanistic. Various articles, including ‘Was Leopardi a scientist?’ in 1976, flowed on to his final book, The Lab and the Labyrinth: Science, the Humanities and the Unity of Knowledge , published in March 2016, just before his final illness.

In addition to his writings on Enlightenment and Romanticism, Carsaniga maintained a passionate interest in language: the Italian ‘Questione della Lingua’, questions of etymology and translation, of grammar and language pedagogy. His language textbooks Just Listen ’N Learn Italian, Breakthrough Italian, Italiano espresso, Incontri in Italia, and Avventura had extraordinary longevity and were revised and reissued by others long after Giovanni had moved on to other projects.

Moral and political values were always immensely important to Giovanni. Although he was quite agnostic he came armed with a solid protestant knowledge of the Bible and no fear of a fight. He was a strong unionist and had been staff union president at Sussex. As a colleague and administrator he was scrupulously fair and straightforward, sometimes clashing with others in his refusal to acquiesce in what he perceived as injustice. He was unfailingly generous to colleagues, students and friends. His collaborations with John Stinson on fourteenth-century music and with Jennifer Nevile on Renaissance dance bear witness to his enthusiasm and support.

Giovanni was born in Milan on 5 February 1934, the son of Arnaldo Camillo Carsaniga, a Methodist minister, and his wife Annamaria Visco-Gilardi. Arnaldo’s first parish was Rapolla, in the province of Potenza, but from 1942 to 1947, he was the Methodist minister in Salerno, just south of Naples, where Giovanni grew up as an only child in the manse, receiving Latin and music lessons from the organist who lived with the family. He became a skilled pianist and continued to play as long as his health permitted. Giovanni attended school first in Naples and then in La Spezia, before matriculating to the University of Pisa. Family history records both heroically Italian experiences: his grandmother received a candy from Giuseppe Garibaldi; and the truly exotic: his maternal grandfather had resided in Bedford Square as private secretary to Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins, author of the archetypal Ruritanian novel, The Prisoner of Zenda.

Giovanni’s first marriage to Anne-Marie Girolami ended in 1974. In 1975, shortly before his move to Perth, he married Pamela Risbey, and her twin sons, Tom and Paul, and her daughter, Greta Scacchi, accompanied them to Perth. Pamela had been a professional dancer in Paris, and ran a dance school in Haywards Heath and taught Italian. They met when Giovanni was recommended by the University of Sussex to take her O-Level students through to their A-Levels.

Giovanni and Pamela had a rare capacity to make new friends, and were initiated into the refined and fiendish game of croquet when they moved to Coogee. They were active walkers and had a smart silver campervan for holidays. Shortly before his retirement Giovanni noticed he was losing strength in his right hand and was diagnosed soon afterwards with a progressive neurological disorder. He brought his retirement forward slightly and he and Pamela returned to the UK, with the intention of dividing their time between their home in Hove and their London flat. By 2012 Giovanni was severely incapacitated by his condition and they moved back to London to a specially adapted home in Kennington where Giovanni continued to take a vigorous interest in all matters social, cultural, and political until the end of his life.

He died on Sunday 27 March 2016 from the complications of a persistent infection. He is survived by Pamela and family in the UK, Italy and Australia.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- </div></li><li class="share-end"/><li class="share-reddit"><div class="reddit_button"><iframe src="https://www.reddit.com/static/button/button1.html?newwindow=true&width=120&url=https%3A%2F%2Facis.org.au%2F2016%2F04%2F04%2Fgiovanni-carsaniga-1934-2016%2F&title=Giovanni%20Carsaniga%20%281934-2016%29" height="22" width="120" scrolling="no" frameborder="0"/></div></li><li class="share-end"/></ul></div></div></div></div></div> <div id="jp-relatedposts" class="jp-relatedposts"> <h3 class="jp-relatedposts-headline"><em>Related</em></h3> </div></div> </div>

Recent News