Nobel-winning Sussex chemist honoured with blue plaques

A University of Sussex scientist who revealed the detailed chemistry of how enzymes work has been honoured with two blue plaques.

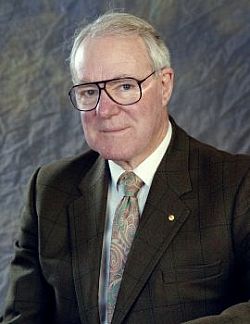

Professor Sir John Cornforth

Professor Sir John Cornforth

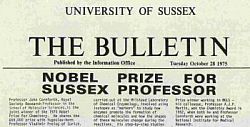

Article published in the Bulletin on 28 October 1975

Article published in the Bulletin on 28 October 1975

Before coming to Sussex in 1975, pioneering chemist Professor Sir John Cornforth spent 13 years at Shell UK’s Milstead Laboratory of Chemical Enzymology, near Sittingbourne in Kent.

At a ceremony in Sittingbourne on 1 April, the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) celebrated Cornforth’s contribution to science at Milstead, where he developed his research on enzyme mechanisms associated with the biosynthesis of cholesterol – work for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1975.

The legacy of Cornforth, who died in 2013, gave scientists a deeper understanding of many of the biochemical cycles that underpin cellular activity and has stimulated research into the pharmacological mediation of these cycles.

Former colleague Professor Jim Hanson says: “Although metal plaques cannot fully encapsulate the memories of a particular time and place and the qualities of the people who worked there, they can provide a permanent reminder of a period of history, and - in the case of Sir John Cornforth - the work of a remarkable scientist.”

Former RSC President, Professor David Phillips, unveiled the two National Chemical Landmark plaques. One will be placed at the Milstead site – now part of the Kent Science Park in Sittingbourne - and the other at Sittingbourne Public Library, which is more accessible for members of the public.

Other speakers at the presentation were Sussex-based Dr Rupert Purchase (from the RSC Historical Group), Cornforth’s younger daughter Philippa, and Professor Hanson, who was a colleague of Cornforth at Sussex for nearly 30 years.

Professor Hanson reminded the 70 guests that Cornforth, born in 1917, graduated from the University of Sydney with the top BSc in 1937. He and his future wife Rita Harradence, both holders of prestigious 1851 Scholarships, sailed from Sydney for England in 1939 to commence their doctoral studies at the University of Oxford. By this time, he knew he would be profoundly deaf for the rest of his life. Rita was to make very significant contributions to Cornforth’s work, including that at Sittingbourne and later at Sussex.

Before the award of his Nobel Prize had been announced in 1975, Cornforth had moved to Sussex, attracted by the prestige of the University, the laboratory facilities and the stimulating intellectual environment.

At Sussex, Cornforth continued a project that he had started with Rita at Sittingbourne. This was to design a compound that might mimic the catalytic properties of an enzyme. For a chemical reaction, Cornforth chose olefin hydration. With a small group of post-doctoral fellows, mainly from his native Australia, he managed to establish a ‘proof of concept’ of his model enzyme system of olefin hydratase before he finally took off his white lab coat in 2005.

Speaking at the unveiling, Professor Hanson described Cornforth as “warm and approachable”.

He added: ““Deafness can be very lonely. Cornforth valued the social environment of the Sittingbourne and Sussex laboratories and the academic friendship of his colleagues.

“Despite his deafness, Kappa [as Cornforth was widely known] had an amazing, almost uncanny ability, not only to pick up what was being said, but also to make apposite and helpful comments. He was generous with his time, to both research students and undergraduates.

“As colleagues watched him work logically through a chemical problem they watched the master chess player that he was, evaluating every possibility methodically, step by step, in order to reach an unambiguous answer.”