Sussex ‘eyeball squad’ helps survey the skies in hunt for dark energy

First-year Physics students at the University of Sussex gave up their summer sunshine to study the stars as part of a major international cosmology survey that began this week (3 September 2013).

Dr Marisa March and one of her team of "eyeballers", physics student Rhys Poulton, who helped test-run images for the Dark Energy Survey. Image: Stuart Robinson

Dr Marisa March and one of her team of "eyeballers", physics student Rhys Poulton, who helped test-run images for the Dark Energy Survey. Image: Stuart Robinson

Dark Energy Camera image of the NGC 1398 galaxy in the Fornax cluster, roughly 65 million light years from Earth and containing more than a hundred million stars. Credit: Dark Energy Survey

Dark Energy Camera image of the NGC 1398 galaxy in the Fornax cluster, roughly 65 million light years from Earth and containing more than a hundred million stars. Credit: Dark Energy Survey

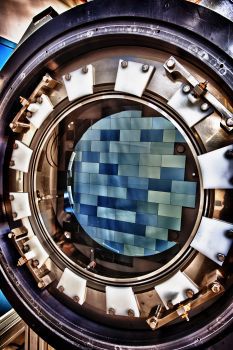

The Dark Energy Camera features 62 charged-coupled devices (CCDs), which record a total of 570 megapixels per snapshot. Credit: Reidar Hahn/Fermilab

The Dark Energy Camera features 62 charged-coupled devices (CCDs), which record a total of 570 megapixels per snapshot. Credit: Reidar Hahn/Fermilab

The 12 students – led by Sussex astrophysicists Dr Marisa March and Dr Kathy Romer – formed part of an “eyeball squad” that studied thousands of test images produced by a new super-camera. The students were searching for anomalies in the images during the run-up to the launch of the Dark Energy Survey (DES).

People, rather than computers, are better for this task as only human eyes and brains can spot unpredicted patterns and inconsistencies – but it means putting in many long hours, staring at computer screens.

DES is a five-year mission to collect images of millions of galaxies, constellations and exploding stars called supernovae, as they evolve across billions of light years.

To do this, scientists are using the world’s most powerful digital camera (the Dark Energy Survey Camera – a 570-megapixel digital camera that includes five lenses, the largest nearly a metre across, that together provide sharp images over its entire field of view) and the giant Blanco 4m telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in the Atacama desert in Chile.

Scientists will use the images gathered to systematically map one-eighth of the sky (5,000 square degrees) in unprecedented detail. The start of the survey is the culmination of ten years of planning, building, and testing by scientists from 25 institutions in six countries, including a team at Sussex.

The survey’s goal is to address some of the fundamental questions of astronomy and physics: why the expansion of the Universe is speeding up, instead of slowing down due to gravity as it should be according to Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, and whether this cosmic acceleration is being caused by the mysterious force known as dark energy.

Dr March says: “Dark energy cannot be seen directly. Instead we look for the effect that dark energy has on other objects in the Universe, such as supernovae and galaxies.

“If you look out of the window, you cannot see the wind, but you can see a flag flying and the trees swaying, so you know the wind is there. So for DES we will be using the Dark Energy Camera to look deep into the Universe at the pattern that galaxies make as they are distributed through the Universe – the brightness of supernovae, the slightly distorted shapes of distant galaxies and the clustering of galaxies. Taken together, all of these signs point to the presence of dark energy. Just like the wind, we cannot see it, but we can see the effect it has on the things around it.

“During this past year some of our students have been checking the 150-300 pictures taken every night of the sky to ensure that they are high quality with no anomalies caused by stray light casting patterns across the picture and no electronic glitches giving strange effects.

“Looking at these images was careful and painstaking work, very time consuming and sometimes very tedious, but it did have its rewards – scanning across these images one can see a wealth of tiny far away galaxies, each one beautiful and different, each one perhaps previously unseen by human eyes.”

Student Rhys Poulton was one of the first-year undergraduate “eyeballers”. He says: “For me, being at university is not just about getting my degree. I wanted to gain skills which cannot be taught in lectures or workshops, so this project gave me a great opportunity to do that. I wanted to be involved so I could be part, however small, of something big. It’s a field of physics I’m passionate about – and this is a project I might want to be involved with in the future, so this has been a brilliant experience.”

During the next four years, DES member Dr Romer and her students will be counting clusters of galaxies, while Dr March will be examining DES supernovae. Both will be using colour images that will be produced by DES of 300 million galaxies, 100,000 galaxy clusters and 4,000 new supernovae, many of which were formed when the universe was half its current size.

Dr March, who will now be moving to America to work on another dark energy project called EUCLID adds: “For me this has been a great opportunity to work with our students at Sussex. It’s exciting being part of such a fantastic international project and it's great that some of our students have been able to share in that and have a chance to work with real data.”

Dr Romer, who researches galaxy clusters and their role in the structure of the Universe, says: “I was delighted by the response of our students. It is testament to their dedication and curiosity that so many of them were prepared to give up their free time to support an astronomy project based half way across the world.”