Sussex neuroscientist explains why we’re hungry for puzzles

A Sussex neuroscientist has come up with a radical new approach in the pursuit of our understanding of consciousness.

In his new book The Ravenous Brain, published yesterday (13 September), Dr Daniel Bor examines how consciousness has been explained in the past – and how his new theory of it being an “accelerated knowledge-gathering tool” could illuminate the mystery that has puzzled philosophers and scientists for centuries.

In his new book The Ravenous Brain, published yesterday (13 September), Dr Daniel Bor examines how consciousness has been explained in the past – and how his new theory of it being an “accelerated knowledge-gathering tool” could illuminate the mystery that has puzzled philosophers and scientists for centuries.

“Our consciousness is the essence of who we perceive ourselves to be,’” says Dr Bor, a research fellow at the Sackler Centre for Consciousness Science. “It is the citadel for our senses, the melting pot of thoughts, the welcoming home for every emotion that pricks or placates us. For us, consciousness simply is the currency of life.”

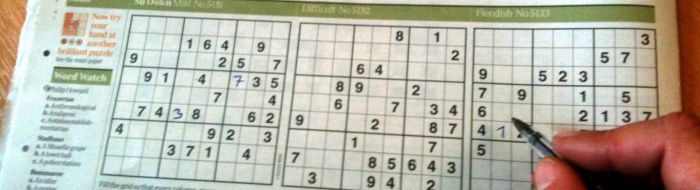

What sets humans apart in the animal kingdom is our ravenous appetite for knowledge, even when all our biological needs are met.

But it’s not just random information. Dr Bor’s new theory postulates that we are looking for structures and patterns, something he calls “chunking”, in which we combine primitive pieces of information we have previously gathered and create something meaningful out of them.

Many of these activities, such as crossword puzzles and sudoku, don’t seem to serve an obvious biological purpose. But Dr Bor argues that it is this puzzle-solving that generates innovation and can lead an animal out of danger, thus saving species from extinction. “In this way, evolution and conscious thought mirror one another,” he says.

However, the advantages of human consciousness also carry the risk of mental fragility. In candid and lucid prose, Dr Bor writes about the consequences of his father’s stroke and his wife’s struggles with a form of bi-polar disorder.

He goes on to challenge preconceptions about mental illness, describing conditions such as attention-deficit disorder, schizophrenia and autism as “disorders of consciousness”.

For example, he observes that disrupted sleep, which can quickly cause disorientation and poor memory function, is likely to be a cause rather than a symptom of some conditions. Methods of treatment for these sufferers could focus more on therapies that tackle underlying sleep abnormalities as well as enhancing states of consciousness.

He concludes with the advice that, although chunking can be enormously advantageous for us, it is also beneficial to practise meditation and temporarily to reject some of the strategies and habits we have developed over the years.

“Without the myriad mental obstacles of those chunks invading our thoughts, we can reacquaint ourselves with how beautiful much of the world really is, and how very easy it is to find intense pleasure and joy within it,” he says.